(New Question of the Week)

From time to time we get a question that is more about words than about math; usually these are about the meaning or origin of mathematical terms. Fortunately, some of us love words as much as we love math. But the question I want to look at here, which came in last month, is about both the word and the math; in explaining why the word is appropriate, we are learning some things about math itself.

But it’s not a line …

Here is Christine’s question:

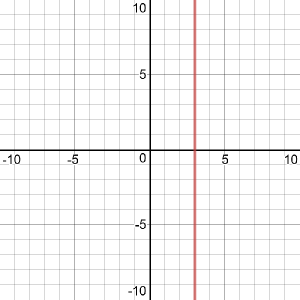

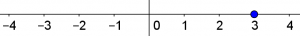

Why is an equation like 2x + 4 = 10 called a linear equation in one variable? Clearly, the solution is a point on one axis, the x-axis, not a line on the two-axis Cartesian coordinate plane? Or are all linear equations in one variable viewed as vertical lines?

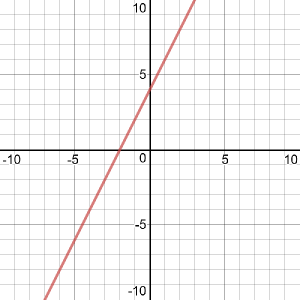

Clearly, she is saying, the phrase “linear equation” means “the equation of a line”. And there is a similarity between the linear equation in one variable above, and a linear equation in two variables, such as \(y = 2x + 4\), which definitely is the equation of a line. But with only one variable, the only way to say that \(2x + 4 = 10\) is the equation of a line is to plot it on a plane as the vertical line \(x = 3\). Is that the intent of the term?

No, it goes further than that, because you also have to consider three or more variables. I initially gave just a short answer, to see what response it would trigger before digging in deeper:

The term “linear”, though derived from the idea that a linear equation in two variables represents a line, has been generalized from that to mean that the equation involves a polynomial with degree 1. That is, the variable(s) are only multiplied by constants and added to other terms, with nothing more (squaring, etc.).

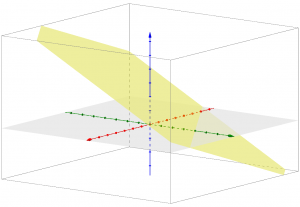

So you could say that the term has been taken from one situation that gave it its name, and applied to more general cases with different numbers of variables. A linear equation in three variables, for example, represents a plane.

From my perspective, “linear” means far more than “having a graph that is a line”. My first thought when I see the word (outside of an elementary algebra class) is “first-degree polynomial”. Although one initially connects it to straight lines, when we extend its use (and almost every idea in math is an extension of something simpler), the idea we carry forward is the degree, not the number of dimensions. For example, here is the beginning of the Wikipedia article about linear equations:

A linear equation is an algebraic equation in which each term is either a constant or the product of a constant and (the first power of) a single variable (however, different variables may occur in different terms). A simple example of a linear equation with only one variable, x, may be written in the form: ax + b = 0, where a and b are constants and a ≠ 0.

Although this article is about linear equations in general, they start with one variable, not with lines. And although they show the graph of a line, the second paragraph skips over the two variable case, right to three variables:

Linear equations can have one or more variables. An example of a linear equation with three variables, x, y, and z, is given by: ax + by + cz + d = 0, where a, b, c, and d are constants and a, b, and c are non-zero.

But why would we call any polynomial equation with degree 1 “linear”, when it is only in two dimensions that it is related to a line? In the one-variable case, as Christine said, the graph is really a point; and in this three-variable case it is a plane:

But, still – it’s not a line!

Christine wasn’t quite convinced:

Thank you so much. I am very particular with terminology when I teach mathematics. I have to say, I do not like this generalization of the term. I think it is misleading.

Hmmm … is the term “linear” misleading? Not to mathematicians, and I would hope not to students once they get used to it. Yet it’s true that it doesn’t quite mean what it seems to say. And is generalization bad? I think it’s the essence of what math is – and also an integral part of languages,which are always extending the meaning of words to cover new needs.

Here is my response:

Hi, Christine.

Thanks for writing back with additional thoughts. Let’s think a little more deeply about it.

First, this is standard terminology that has been in use for 200 years by many great mathematicians, so we should be very careful about considering it a bad idea. I don’t think you’re likely to convince anyone to change; the word is used not only of a linear equation in itself, but of “systems of linear equations” (in contrast to “non-linear equations”); of the whole major field of “linear algebra”; and for related concepts like “linear combination”, “linear transformation”, and “linear independence”, all of which apply to any number of variables or dimensions. So the term is very well established with a particular but broad meaning, and (at least after the first year) no one is misled by it. We know what it means, and what it means is more than just “line”.

Second, what would you replace it with? If you don’t want to use the word “linear” except in situations that involve actual lines, what word would you use instead to describe the general class of equations involving variables multiplied only by constants, regardless of the number of variables? We need a word for this bigger idea; that word will either be a familiar word whose meaning is stretched to cover a bigger concept, or some made-up word. The tradition in math has always been to take familiar words and give them new meanings (either more specific, like “group” or “combination” or “function”, or more general, like “number” or “multiplication” or “space”). So what we observe here is found throughout mathematics: a word that has grown beyond its humble beginnings. (This is also true of the entire English language! Most words would be “misleading” if you thought too deeply about their origins.)

I could say that, in a sense, all of mathematics is about generalization (or abstraction). I just mentioned “number”; some people do complain about calling anything other than a natural number a “number”, but the logical development from natural numbers, to integers, to rational numbers, to real and complex numbers, involves repeated broadening of the term, which has been extremely useful. We invent new concepts, and give them old names because they are a larger, more powerful version of the old concept.

I mentioned how common it is in English for a word to grow beyond its original meaning. Sitting here at my computer, I look at the mouse – is it misleading to call it that when it doesn’t have legs, and may not even have a tail? And the computer has a screen; at one time, a screen was a flat surface that hid something that wasn’t to be seen (or that kept out bugs); then it was applied to flat surfaces on which pictures were projected; and then to a surface that shows a picture itself. Is that misleading? It would be if you went back a hundred years …

And thinking again about math terms, I’m reminded of this discussion where I pondered what all the different operations that are called “multiplication” have in common.

So how do we explain it?

But as I wrote this, I realized that I had gone off in a different direction than Christine, and I wanted to relate my answer to her specific context, linear equations in one variable. The real question was pedagogical: How could she explain this to her students, so that (eventually) “linear” would mean to them what they will need it to mean? I continued:

Now, I’ve been mostly thinking of the “enlarging” development of the word “linear”, taking it to more than two dimensions; you’re thinking specifically of the term used with only one variable. So it may help if we focus on that, to fit your particular context. I’d like to explain linear equations in one variable in a way that should make it clear why we use the word, and that it is not a misnomer.

Consider the equation you asked about, 2x+4=10. The left-hand side is an expression; we call it a linear expression, because if you used it in an equation with two variables, y = 2x+4, its graph would be a straight line. So we call 2x+4 a linear expression (or, later, a linear function). A linear equation in one variable is one that says that two linear expressions are equal (or one is equal to a constant).

Or, to look at it another way, one way to solve this equation would be to graph the related equation y = 2x+4, and find where that line intersects the line y = 10. So the linear equation can be thought of very much in terms of a line.

(If this were a student’s first exposure to linear equations in one variable, she likely wouldn’t have seen graphs of lines yet, and wouldn’t be ready for this discussion; either the word linear would be used without explanation yet, or we would hold off on the word until later.)

Does this help?

It’s often hard to be sure what kind of answer will help; but Christine gave the answer I hoped for:

Yes, your response does help very much. In addition, it gives me a lot to think about. It is true, the grade level I am currently teaching does learn to solve linear equations in one variable before they learn about linear equations and functions. Perhaps this is why I question the use of the term. I must remember that I have had experience in mathematics beyond their years, and therefore, am more thoughtful about what terms they are exposed to and more importantly in what sequence the mathematics is presented to them. I thank you again for such an in depth response and will certainly give this discussion much more thought. It is a pleasure speaking with you.

I imagine if I were introducing these equations to students with no exposure to graphs of lines, I might just mention in passing that these are called “linear equations in one variable”, and that we would soon be seeing why the word “linear” is appropriate. For now, what it means is that all we do with the variable is to multiply it by a constant, and to add things. Kids are used to hearing things they’ll understand later …

Very interesting article, Dr.Peterson!

Just wanted to ask, so then why are polynomials of the second degree quadratics? ‘Quad’ reminds me of 4 (quadrilateral is a shape with 4 sides, a quadrant is 1/4 of a circle)

And what’s the difference between an identity and an expression?

Hi, Sarah.

First, the “quad” issue is another common question; for an answer, start here: Names of Polynomials

Second, an identity is not an expression, but an equation (that is, a statement that two expressions are equal). In particular, it is an equation that is true for any value of the variable(s) it contains. For instance, a+b = b+a is an identity.

Thank you, Dr.Peterson!

Could call it “first order equation with one variable”. That seems unambiguous and intuitive.

Certainly there are several things we do call this equation, and “first order” (or “first degree”) is among them. Moreover, it does answer my question, “What would you replace it with?” in any number of variables. I suppose the standard usage of “linear” has to be explained by another common feature of languages that I didn’t mention: the tendency toward economy, shortening or simplifying commonly used words or phrases to save time or effort!

So, yes, we could do without the term “linear” at all, and always use a two- or three-word phrase rather than a single word; but we don’t.

In any case, of course, the question, as I take it, was not “Why must we use the word ‘linear’ here?”, but “Why is the word ‘linear’ applicable here?”

I think the headings in this article tell the story “But it’s not a line…”, “But, still – it’s not a line!”, “So how do we explain it?”. I think it is not unreasonable to expect something called a “linear equation” to be an equation describing a line, for the simple reason that *words are supposed to mean things.*

“Hmmm … is the term “linear” misleading? Not to mathematicians […] Yet it’s true that it doesn’t quite mean what it seems to say.” But “not meaning what it seems to” is what misleading *means!* Using inaccurate language to serve existing convention may economical. It can even be precise. But we should not delude ourselves into thinking this is a good name for the concept.

You are missing a key thing I said, just after what you quoted:

“Yet it’s true that it doesn’t quite mean what it seems to say. And is generalization bad? I think it’s the essence of what math is – and also an integral part of languages, which are always extending the meaning of words to cover new needs.”

Whenever you speak, you are constantly using words that “don’t mean what they seem to say”! Your comment is similar to the “etymological fallacy“, which supposes that any word means exactly what its origin implies. For example, the word “September”, which originally meant “seventh month”, was retained though the months were renumbered, making it now the ninth. I doubt that you insist it is wrong to use that name, just because it is conventional.

It is quite normal for a word to grow from an original meaning to related concepts that are either more general (as here) or more specific, or just shifted (like September). This is called “semantic change“, and I illustrated it later with the words “mouse” and “screen”. In the case of mathematical terminology, generalization is essential, just as it is in technology.

If you prefer to use longer phrases in place of “linear”, feel free to do to. Just be aware that you will see the word “linear” meaning “first-degree polynomial”, and that there is a reason for this development of meaning.

Pingback: Does a Linear Function Have to be Continuous? – The Math Doctors

“A first degree equation is linear equation.” Is this small definition with an example is correct if someone ask what is linear equation? I know I can elaborate the answer but I am curious if this small definition is correct or not?

Yes, a linear equation can be defined as a first degree equation. That is true whether we are talking about an equation in one variable or more.

I saw in every definition of linear equation with multiple variable (say 3) “A linear equation is of the form ax+by+c=0”, but is it necessary to add these coefficient a, b, c ? Because these coefficients does not effect linearity of the equation (from my point of view). With respect to Vector space and Field, if we treat these coefficient as scalar then they (scalars) are only used to scale the value of vectors.

However in any case, say if we need these scalars in the above definition of linear equation, what about if we choose scalars as binary field elements (0,1)? In such case, can we defined linear equation without these coefficients a,b,c (provided field is binary)?

If you omit a, b, and c, and write x+y=0, then you are in effect specifying a=1, b=1, c=0. This is a linear equation; but it is not a definition, as not every linear equation has this form. The parameters are needed in order to write a general form that applies to all linear equations (in two variables, in this case).

If x and y were vectors (which is not what this equation would usually mean), then a and b would be scalars, but c would have to be a vector. The scalars would be important, not “only used to scale”!

If you are working within a vector space over a field other than the real numbers, that doesn’t change anything. But how is the set {0,1} a field? Are you referring to this?

This is turning into a discussion that would work better as a submitted question rather than as a comment. If you need more help, please submit it at our Ask a Question page.

Thanks a lot Dr. Peterson for giving me time to understand this clearly. Yes, I meant to say GF(2) but I wrote it in a wrong way.

What about Linearity? You mean, then, that something that is called linear, as y=ax+b, may not necessarily hold Linearity properties?

I suppose you are referring to the concept of a linear map as discussed here in Wikipedia. You are correct. In that sense, y = ax+b is considered affine, rather than linear.

Linearity in this sense is different from linear functions in the sense discussed here. For some discussion of the distinction, see my more recent post Does a Linear Function Have to be Continuous?

The equation y=10 is really linear or just they included in linear equations because this have just one variable for graphing in two dimensions it must have two variable ?

As I said in the post, a linear equation (regardless of the number of variables) is one involving polynomials of degree 1, so y = 10 is linear. It is interesting in that it could be either an equation in one variable, y (in this case, one that is already solved), or an equation in two variables, which can be graphed as a horizontal line (because it “doesn’t care” about the value of x, so x can be anything). But either way, it is a linear equation.

Thank you so much for explaining to me why a linear equation is called a linear equation! You made it clear that x+4=10 can expressed on a line on the coordinate plane much as 2x+4=10 can be.

Then, you clarified to me that y+4=10 would also be expressed as a line or linear form on the graph.

Equally significant is that you explained how two variables can also be expressed as linear such as:

y=2x+4. In this values of one of the variables have to be proposed on a table such as-let x have 1, 0,-1 in order to solve for y variable. The y=x+4 also brings in the y-intercept idea. It is interesting how you then connected the three rules or formula of linear equation,namely: slope intercept formula, y=mx +b; standard formula- Ax + By=C and by extension point slope formula, M=y2-y1/x2-x1. You are a genius, Dr Peterson. point slope formula originates from coordinates of ordered pairs on the graph.

The way you express this is misleading, and brings up something another reader asked as a question on the site, which deserves to be mentioned. While it is true that 2x+4=10 graphs as a line on the xy-plane, as I showed in the post, the same can be said of x^2+4=10, which is not a linear equation! We don’t judge linearity of an equation from its graph alone.

I don’t see that I mentioned the different forms for a line in this post; but for other content on standard and point-slope forms, you might find these helpful:

Standard Form of a Line

Equation in Slope Intercept or Point Slope Form

Formulas for the Equation of a Line

Could you conclude why are they called “linear equations” ?

I think I did.

Is there something you think needs to be added?