Last time, we saw several problems where we were given remainders when an unknown polynomial was divided by two or three linear polynomials, and had to find the remainder on division by the product of those divisors. Here we’ll look at a recent question, and an older one, that add a twist: we’ll be given remainders on division of an unknown polynomial by non-linear divisors, and find the remainder when it is divided by a polynomial that is not the product of the others. Do our methods still work?

A square divisor

This question came from Amia in October:

Hi Dr Math,

I have the question below and non-complete solution.

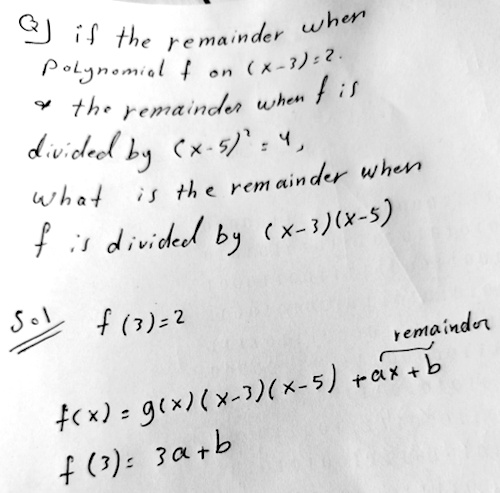

Can you help me to solve it completely? I need another equation to find a and b .

Thank you in advance.

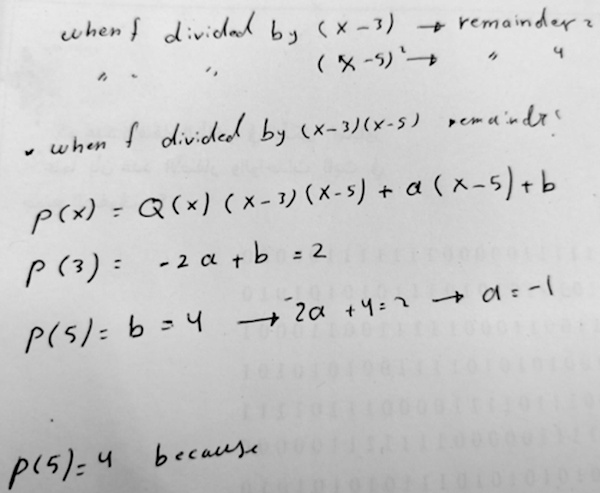

So the problem is to find the remainder when \(f(x)\) is divided by \((x-3)(x-5)\), given that $$f(x)=p(x)(x-3)+2\\f(x)=q(x)(x-5)^2+4$$ This differs from the problems we saw last time, in that the second divisor is not linear, and the final divisor is not the product of the two initial divisors. It’s also interesting that, in principle, the second given remainder could have been linear rather than the constant 4 – though 4 is a perfectly good polynomial with degree less than 2.

Amia is using the method I called “undetermined coefficients” last time: The remainder theorem tells us that if the remainder on division by \((x-3)\) is 2, then \(f(3)=2\); and the remainder of a division by a quadratic must be (at most) linear, allowing us to assume that the desired remainder is \(ax+b\). So what he’s written so far implies that $$3a+b=2$$

But evidently he is stopped by the new feature of this problem, the division by a square.

I answered after giving the problem more time than usual:

The quick answer is that the second equation you need is f(5) = 4. That quickly gives a solution.

I have spent too much additional time trying to confirm that there is such a function, and that the extra fact that 5 is a double root of f(x) – 4 = 0 doesn’t change things. I still haven’t completed that thought, but I don’t want to wait longer before answering.

I have seen questions of this sort before, but they seem to be taught explicitly in other countries more than they are in my own experience, so there is probably more to say about the problem than I know without doing some research. I’ll do that when I have time (I hope).

I had not yet discovered the discussions we looked at last time, which give a variety of approaches to more typical problems; I just recalled seeing such problems in the past, and recognized that this is a little different.

We’ll discuss below, why my claim is true, and is all we need; but it implies that \(f(5)=5a+b=4\), so we need to solve the system $$3a+b=2\\5a+b=4$$

We find that \(a=1\) and \(b=-1\), so our remainder is \(x-1\).

But my concern was that this work, and this answer, are exactly what we would have done if the second division had been merely by \((x-5)\); shouldn’t this problem have a different answer? Further (though I didn’t quite see this then), in the problems last time, the remainder we found was itself one possible polynomial we could have started with, whereas, as we’ll see below, that is not true in this problem. It was conceivable that this solution could be vacuous, in the sense that it would be a “true” conclusion about something that doesn’t actually exist. Moreover, it is not clear that the remainder is the same for all \(p(x)\) that satisfy the given conditions – that is, that it is unique. We’ll look at those questions after (tentatively) solving the problem.

Amia replied with a different expression for the remainder, which makes the system of equations a little simpler:

I made this trial:

(Halfway through this he seems to have changed the unknown polynomial from \(f(x)\) to \(p(x)\). I’ll be using that name in what follows.)

His work should have shown \(a=1\) rather than \(a=-1\), so his remainder should be \(1(x-5)+4=x-1\), agreeing with our work.

I answered, hinting at that correction, and explaining why \(p(5)=4\):

I infer that your answer is that the remainder is a(x-5)+b = -1(x-5)+4 = 9 – x. That disagrees with the answer I got by a more direct method. (Check your signs.)

As for the question in the last line, since the remainder on division by (x-5)2 is 4, we know that p(x) = (x-5)2q(x) + 4, so

p(5) = (5-5)2q(5) + 4 = 4.

Note that division by a quadratic factor \((x-5)^2\) could leave a linear remainder, but a constant, though a special case, is entirely normal.

We didn’t get a reply; probably this was all he needed. But let’s do some more thinking.

Does such a polynomial exist?

My hesitation was partly due to the specialness of the remainder. In the problems we looked at last time, the remainder we found could work as the original polynomial, since the final divisor was always the product of the initial divisors, so adding any multiple of that product to the remainder would result in the desired remainders. That settled the question of existence, by providing an instance. Here, the final divisor, \((x-3)(x-5)\), is not a multiple of \((x-5)^2\), so it isn’t so simple. In particular, if we just divide our remainder \(x-1\) by \((x-5)^2\), the remainder is \(x-1\), not 4.

It seems unlikely that there would be no polynomial satisfying the conditions, but it was worth thinking about. So let’s try to find the simplest \(p(x)\) we can. We need $$p(x)=f(x)(x-3)+2\\p(x)=g(x)(x-5)^2+4$$ The simplest quotient we could have is a constant \(g(x)=k\); then $$p(x)=k(x-5)^2+4=kx^2-10kx+25k+4$$

Dividing this by \((x-3)\), we get $$kx^2-10kx+25k+4=(kx-7k)(x-3)+(4k+4)$$ Setting the remainder to 2, we get $$4k+4=2\\k=-\frac{1}{2}$$ So our polynomial is $$p(x)=-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}$$

To check this, do the divisions! We get$$-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}=\left(-\frac{1}{2}x+\frac{7}{2}x\right)(x-3)+2\\-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}=\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)(x-5)^2+4\\-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}=\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)(x-3)(x-5)+x-1$$

So there is such a polynomial, and our remainder \(x-1\) is correct for this example.

Solving the problem by substitution

We saw two or three other ways to solve problems last time; let’s try this one by substitution (which I called using the Remainder Theorem).

Again, we are given that $$p(x)={\color{Red}{f(x)(x-3)+2}}\\p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{g(x)(x-5)^2+4}}$$

Setting these equal, we have $${\color{Red}{f(x)(x-3)+2}}={\color{SeaGreen}{g(x)(x-5)^2+4}}$$

We have two ways to go from here, eliminating either f or g. It turns out differently in each case, so I’ll do both.

First, eliminating g by setting \(x=5\), we get $$f(5)(5-3)+2=g(5)(5-5)^2+4\\2f(5)+2=4\\f(5)=1\\f(x)={\color{Blue}{h(x)(x-5)+1}}$$

Substituting, $$p(x)={\color{Red}{f(x)(x-3)+2}}\\=\left[{\color{Blue}{h(x)(x-5)+1}}\right](x-3)+2\\=h(x)(x-5)(x-3)+(x-3)+2\\=h(x)(x-5)(x-3)+x-1,$$ so the desired remainder is \(x-1\), as before,

If, instead, we eliminate f by setting \(x=3\), we get $$f(3)(3-3)+2=g(3)(3-5)^2+4\\2=4g(3)+4\\g(3)=-\frac{1}{2}\\g(x)={\color{Blue}{k(x)(x-3)-\frac{1}{2}}}$$

Substituting, $$p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{g(x)(x-5)^2+4}}\\=\left[{\color{Blue}{k(x)(x-3)-\frac{1}{2}}}\right](x-5)^2+4\\=k(x)(x-3)(x-5)^2-\frac{1}{2}(x-5)^2+4\\=k(x)(x-3)(x-5)^2-\frac{1}{2}(x^2-10x+25)+4\\=\left[k(x)(x-5)\right](x-3)(x-5)-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}$$

You might think that this means the remainder is \(-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}\) (does that look familiar?), but the remainder has to have degree less than the degree of the divisor, namely 2. So we have to divide \(-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}\) by \((x-3)(x-5)\), and it turns out (as we saw in our check above) that $$-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}=-\frac{1}{2}(x-3)(x-5)+x-1$$ So we get the same remainder after all:

$$p(x)=\left[k(x)(x-5)-\frac{1}{2}\right](x-3)(x-5)+x-1$$

Solving it by the Chinese Remainder Theorem

Can we also solve the problem by the Chinese Remainder Theorem? Here is how Wikipedia states the theorem for polynomials:

The Chinese remainder theorem for polynomials is thus: Let \({\displaystyle P_{i}(X)}\) (the moduli) be, for \({\displaystyle i=1,\dots ,k}\), pairwise coprime polynomials in \({\displaystyle R=K[X]}\). Let \({\displaystyle d_{i}=\deg P_{i}}\) be the degree of \({\displaystyle P_{i}(X)}\), and \({\displaystyle D}\) be the sum of the \({\displaystyle d_{i}.}\) If \({\displaystyle A_{i}(X),\ldots ,A_{k}(X)}\) are polynomials such that \({\displaystyle A_{i}(X)=0}\) or \({\displaystyle \deg A_{i}<d_{i}}\) for every i, then, there is one and only one polynomial \({\displaystyle P(X)}\), such that \({\displaystyle \deg P<D}\) and the remainder of the Euclidean division of \({\displaystyle P(X)}\) by \({\displaystyle P_{i}(X)}\) is \({\displaystyle A_{i}(X)}\) for every i.

This guarantees the existence and uniqueness of the polynomial \(p(x)\) (with degree 2), and applies despite the squared divisor, because the divisors are still relatively prime; and the same method can be used to solve it. On the other hand, it doesn’t explicitly ensure that the remainder will be the same in all cases; the new divisor, not being a multiple of the given divisors, has a lower degree than the promised p. But we can still use the same method to find p, which will have degree 2 for our problem, and determine what the remainder will be. Hopefully we can prove that it is unique – that is, that all \(p(x)\), of any degree, leave the same remainder.

Recall that we first find polynomials \(a(x)\) and \(b(x)\) such that $$\frac{1}{(x-3)(x-5)^2}=\frac{a(x)}{x-3}+\frac{b(x)}{(x-5)^2}$$ and then use them to write an expression for the desired remainder. So we can write $$\frac{A}{x-3}+\frac{Bx+C}{(x-5)^2}=\frac{1}{(x-3)(x-5)^2}$$ and clear fractions to get $$A(x-5)^2+(Bx+C)(x-3)=1.$$ This expands to $$Ax^2-10Ax+25A+Bx^2+(C-3B)x-3C=1\\(A+B)x^2+(-10A-3B+C)x+(25A-3C)=1.$$

Setting coefficients equal, we obtain $$A+B=0\\-10A-3B+C=0\\25A-3C=1$$

Solving, $$A=\frac{1}{4},B=-\frac{1}{4},C=\frac{7}{4}.$$

Now the remainder we want will be found by multiplying each term in \(A(x-5)^2+(Bx+C)(x-3)\) by the corresponding given remainder: $$r(x)={\color{Red}2}A(x-5)^2+{\color{Red}4}(Bx+C)(x-3),$$ so we have $$r(x)=2\left({\color{SeaGreen}{\frac{1}{4}}}\right)(x-5)^2+4\left({\color{SeaGreen}{-\frac{1}{4}}}x+{\color{SeaGreen}{\frac{7}{4}}}\right)(x-3)\\=-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}$$ as before.

Again, we need to take an extra step to obtain the actual remainder of \(x-1\).

Is the remainder unique?

We still have to deal with the uniqueness issue: Can we be sure that for every polynomial \(p(x)\) that satisfies the conditions, we will get the same remainder from the last division? As we just saw, the Chinese Remainder Theorem applies to this problem, and implies that there is a unique quadratic polynomial \(p(x)\) satisfying the requirements, which clearly is what we just found. Can we show that any larger such polynomial must yield the same remainder? (Note that the CRT itself says nothing about this remainder.)

Let’s call the polynomial we found \(p_1(x)\): $$p_1(x)=-\frac{1}{2}x^2+5x-\frac{17}{2}$$ Any other polynomial satisfying the conditions must differ from this by a multiple of both \((x-3)\) and of \((x-5)^2\), and therefore by their product: $$p(x)=p_1(x)+h(x)(x-3)(x-5)^2$$ Since this also differs by a multiple of \((x-3)(x-5)\), it will leave the same remainder by that division.

But our original work in deriving the remainder was enough to convince us that only this remainder can work.

An exercise for the reader

Just for fun, I wanted to make a problem where that second remainder is not a constant (making it more typical). Try this:

When polynomial \(p(x)\) is divided by \((x-3)\), the remainder is 13.

When it is divided by \((x-5)^2\), the remainder is \(8x-15\).

What is the remainder when \(p(x)\) is divided by \((x-3)(x-5)\)?

The work is no harder than the original problem, but, again, with a little further twist. And to create this problem, I had to do nothing more complicated than picking a \(p(x)\) and doing two divisions (and a third to know the answer).

Quadratic divisors

The other problem is from 1997; here all the divisors are quadratic:

Dividing Polynomials The polynomial p(x) with integer coefficients satisfies: (1) if p(x) is divided by x^2-4x+3, the remainder is 65x-68 (2) if p(x) is divided by x^2+6x-7, the remainder is -5x+a (a) Find the number a. (b) Suppose that p(x) is divided by x^2 + 4x - 21. Find the remainder. I got as far as factoring the two divisors in (1) and (2). I can see that they have the common factor (x-1), but from here I am not sure where to go with it. I noticed that the last equation in (b) has factors (x-3) and (x+7), which are the same factors that the two prior equations don't have in common. This was on a college entrance exam for Japanese high school students.

Here are the factorizations:

$$x^2-4x+3=(x-1)(x-3)\\x^2+6x-7=(x-1)(x+7)\\x^2+4x-21=(x-3)(x+7)$$

Doctor Charles answered:

You seem to have found everything that I found out but haven't yet put all the information to good use. When you say that the remainder when p(x) is divided by q(x) is r(x), it means that we can find a polynomial (in this question we can never tell what it is), let's call it h(x), such that: p(x) = h(x) * q(x) + r(x) In our case, where m(x) and n(x) are two more polynomials which we can't tell anything more about, we have: p(x) = m(x) * (x^2 - 4x + 3) + 65x - 68 p(x) = n(x) * (x^2 + 6x - 7) - 5x + a Because we can't tell anything about m(x) and n(x), it would be good to get some equations that don't make use of them.

After factoring, this says that $$p(x)={\color{Red}{m(x)(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68}}\\p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x)(x-1)(x+7)-5x+a}}$$

This is quite easy as you have already factorized the two divisors so that you should have (x^2 - 4x + 3) = (x-1)(x-3). Now if we put x = 1 or x = 3 in the top equation, the quadratic just evaluates to 0 so we get (respectively):

p(1) = m(1) * 0 + 65 * 1 - 68 = 0 - 3 = -3

p(3) = m(3) * 0 + 65 * 3 - 68 = 0 + 195 - 68 = 127

So the first division gives us two values for the polynomial, since the divisor has degree 2.

If we try the same trick with the second equation we get:

p(1) = n(1) * 0 - 5 * 1 + a = a - 5

p(-7) = n(-7) * 0 - 5 * (-7) + a = 35 + a

But now we have two equations for p(1) so we know:

-3 = p(1) = a - 5

so

a = 5 - 3 = 2

We have p(-7) = 35 + 2 = 37

So the common factor let us find the value of a (= 2) as required, and we have three values of the function, $$p(1)=-3\\p(3)=127\\p(-7)=37$$

Now we can use the undetermined coefficient approach:

Now for the last part. We know that the remainder is a linear term that is something like bx + c. This is just because it is a factor whose degree is one less than the quadratic. (If we had a remainder like ex^2 + fx + g, we could take off another e*(x^2 + 4x - 21) to get something which looked like bx + c.) So we have: p(x) = k(x) (x^2 + 4x - 21) + bx + c k(x) is yet another polynomial about which we know nothing! As you found out, (x^2 + 4x - 21) = (x + 7)(x - 3)

So we want to find b and c in $$p(x)=k(x)(x+7)(x-3)+bx+c$$

So putting in 3 and -7 like before we get:

p(3) = k(3) * 0 + b * 3 + c

p(-7) = k(-7) * 0 + b * (-7) + c

We already have values for p(3) and p(-7). They are 127 and 37. So:

127 = 3b + c

37 = -7b + c

Subtracting we get:

90 = 10b

This means that b = 9. Putting that back in we get 37 = -63 + c so c = 100.

Thus the remainder when p(x) is divided by (x^2 + 4x - 21) is 9x + 100.

So it appears that the required remainder is \(9x+100\). And most likely, there really are polynomials \(p(x)\), making this a valid answer. Can we be sure?

Does such a polynomial exist?

Again, we can’t just let \(p(x)=9x+100\); that doesn’t satisfy the given conditions. In order to confirm this answer, we’ll need to find a polynomial that satisfies the condition, and confirm the conclusion. The simplest possible case would be if the quotients were both constants; so let’s hope for that: $$p(x)={\color{Red}{m(x^2-4x+3)+65x-68}}\\p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x^2+6x-7)-5x+2}}$$

Setting these equal, and expanding, $${\color{Red}{m(x^2-4x+3)+65x-68}}={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x^2+6x-7)-5x+2}}\\mx^2+(65-4m)x+(3m-68)=nx^2+(6n-5)x+(2-7n)$$ For these to be the same polynomial, the coefficients must be equal: $$m=n\\65-4m=6n-5\\3m-68=2-7n$$

The solution of this system is \(m=n=7\). And in fact, $$p(x)={\color{Red}{7(x^2-4x+3)+65x-68}}=7x^2+37x-47\\p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{7(x^2+6x-7)-5x+2}}=7x^2+37x-47$$ So this polynomial satisfies the two conditions; and when we divide by the third divisor, we find that the quotient is again 7, and $$p(x)=7(x^2+4x-21)+9x-100=7x^2+37x-47$$

So there is such a polynomial, and the remainder for this example (the simplest of many) is what we determined.

Solving it by substitution

Now let’s trying using our substitution method on this problem. We know that $$p(x)={\color{Red}{m(x)(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68}}\\p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x)(x-1)(x+7)-5x+2}}.$$

As before, we set these equal and eliminate one quotient by letting \(x=3\): $${\color{Red}{m(x)(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68}}={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x)(x-1)(x+7)-5x+2}}\\m(3)(3-1)(3-3)+65(3)-68=n(3)(3-1)(3+7)-5(3)+2\\127=20n(3)-13\\n(3)=7\\n(x)={\color{Blue}{s(x)(x-3)+7}}$$

Now we substitute this into what we know: $$p(x)={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x)(x-1)(x+7)-5x+2}}\\=\left[{\color{Blue}{s(x)(x-3)+7}}\right](x-1)(x+7)-5x+2\\=s(x)(x-3)(x-1)(x+7)+7(x-1)(x+7)-5x+2\\=s(x)(x-3)(x-1)(x+7)+7(x^2+6x-7)-5x+2\\=s(x)(x-1)(x-3)(x+7)+7x^2+37x-47$$

But we want the quotient and remainder on division by only \((x-3)(x+7)\), so we divide our remainder by that: $$7x^2+37x-47=7(x-3)(x+7)+9x+100$$ Our division is therefore $$p(x)=s(x)(x-1)(x-3)(x+7)+7(x-3)(x+7)+9x+100\\=\left[s(x)(x-1)+7\right](x-3)(x+7)+9x+100$$ and our remainder is \(9x+100\).

We could instead have eliminated the other quotient, by letting \(x=-7\): $${\color{Red}{m(x)(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68}}={\color{SeaGreen}{n(x)(x-1)(x+7)-5x+2}}\\{\color{Red}{m(-7)(-7-1)(-7-3)+65(-7)-68}}={\color{SeaGreen}{n(-7)(-7-1)(-7+7)-5(-7)+2}}\\80m(7)-523=37\\m(7)=7\\m(x)={\color{Blue}{t(x)(x+7)+7}}$$

Now we substitute this into what we know: $$p(x)={\color{Red}{m(x)(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68}}\\=\left[{\color{Blue}{t(x)(x+7)+7}}\right](x-1)(x-3)+65x-68\\=t(x)(x+7)(x-1)(x-3)+7(x-1)(x-3)+65x-68\\=t(x)(x-1)(x-3)(x+7)+7(x^2-4x+3)+65x-68\\=t(x)(x-1)(x-3)(x+7)+7x^2+37x-47$$

But we want the quotient and remainder on division by only \((x-3)(x+7)\), we divide our remainder by that: $$7x^2+37x-47=7(x-3)(x+7)+9x+100$$

Our division is therefore $$p(x)=t(x)(x-1)(x-3)(x+7)+7(x-3)(x+7)+9x+100\\=\left[t(x)(x-1)+7\right](x-3)(x+7)+9x+100$$ and our remainder is, again, \(9x+100\).

The Chinese Remainder Theorem, on the other hand, does not apply to this problem, as the given divisors are not relatively prime. So we can’t use it to solve the problem, and it doesn’t tell us anything about uniqueness. But we don’t need to, since we showed what the remainder must be.

Pingback: Vacuous Solutions: Correct, But Not Really – The Math Doctors