One of the best ways to get people eager to do something is to tell them it can’t be done. When people who are not well-versed in mathematics learn that it is impossible to trisect an angle with compass and straightedge, they sometimes seem to make it their life goal to “do the impossible”. The result is frequent challenges to that assertion in our FAQ, “Impossible” Geometric Constructions. We’ll look today at several of our attempts to clarify what it means in math to say something is impossible, and to answer those who claim to have done it (people called “trisectors”).

What it is that can’t be done

We’ll start by looking at an early statement of the issue, from 1996:

Trisecting an Angle I've recently been pondering the possibility of trisecting an angle. I wasn't sure if it was possible and found a FAQ submitted to you that stated it was indeed impossible. Has it been proved to be impossible or is it that no one has proved it possible? The reason I ask is that I think (but am not sure) that I have found a way to trisect an angle. I am a seventh grade math teacher, so I am not completely ignorant of mathematical proofs. I would appreciate some information on who would be the best person to contact with my "proof". I hope you believe me because I think this actually works.

This is the benign species of trisector, one who just isn’t sure what it is that was proved, and isn’t insisting that everyone else is wrong. Doctor Tom answered, presenting the key ideas one by one:

There is, in fact, a proof that a trisection is impossible. Many people think they have found trisections, but they either don't understand exactly what the problem is or their method is flawed. The problem requires the construction of the trisection using an (unmarked) straightedge and a compass. If, for example, you were allowed to make 2 marks on the straight-edge, there is a trisection. The straight-edge can only connect points already constructed, or use arbitrary points, and the compass can only be used similarly. An exact trisection in a finite number of steps is also required since it's easy to do a trisection that doesn't require too much accuracy. As a limiting case, it might be possible to perfectly trisect an angle in an infinite number of steps.

So what was proved impossible is a specific task using specific methods; if you break the restrictive rule on what tools are available and how they are to be used, trisection is not impossible. For discussions of two such alternative tools, see

Trisecting an Angle: Proof Trisecting an Angle Using the Conchoid of Nicomedes

(The first of these has a broken link that should now be http://www.faqs.org/faqs/sci-math-faq/trisection/. The second has a link that is now http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/HistTopics/Trisecting_an_angle.html.)

So how was it proved to be impossible?

The proof that it's impossible basically considers the arithmetic form of the points that can be obtained using a compass and straight-edge. In a sense, they are "quadratic" devices - the new points generated are solutions of quadratic equations of previously constructed points. So you can clearly get things like square roots, fourth roots, eighth roots, and so on (and it's a bit more complicated than that - what you can get are field extensions of degree 2 over whatever you begin with). But you CANNOT solve irreducible cubic equations this way - such solutions require extensions of degree 3, and no combination of multiples of 2 gives a multiple of 3 (to put it in an inexact, but hopefully clear, way). You can, beginning from nothing, construct a 60 degree angle. So if you can trisect anything, you can trisect the 60 degree angle which you produce. So if you have a trisection, you can construct, from scratch, a 20 degree angle. Hence you can construct the sine and cosine of 20 degrees. But it's easy to show that the sine and cosine of 20 degrees are roots of an irreducible cubic equation over the rational numbers. This is a contradiction, so a trisection is impossible. To get the details, read about fields and field extensions in an abstract algebra book.

One excuse many trisectors give for doubting the proof is that they think algebra can say nothing about geometry. But it can!

As for this teacher’s claimed trisection,

So the bottom line is, there's probably something wrong with your trisection, not because I've seen it, but because I've studied field extensions and irreducibility.

That idea, “I know it’s wrong without needing to see it,” angers a lot of people; but that’s how math works!

The start of an obsession

Here’s another trisection attempt of the relatively benign variety, from 1999:

Attempt at Trisecting an Angle We have a bisector of an angle of 30 degrees (or any degree) that extends into the angle 1" and extends outside the angle 2". Then we have bisector line 3" long. From the vertex of the angle, a circle with a 1" radius is drawn. Then 2" outside the angle, and on the bisector, a circle with a 3" radius is drawn. The two circles meet on the bisector of the angle 1" inside the angle. Question: Are the arcs of the two circles within the angle the same length? Arc a-b of small circle = arc A-B of larger circle. Both arcs are 1" within the angle.

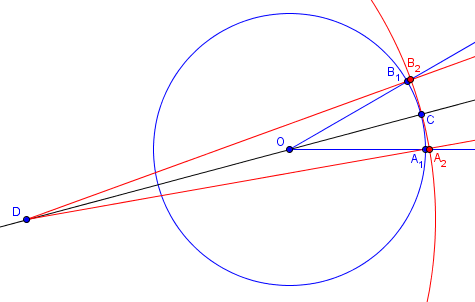

Hollis doesn’t come right out and say he’s doing the impossible; here is a picture of his work, so you can see what he is doing (using A1, B1, A2, B2 for his a, b, A, B):

I responded first by noting that the arcs are not, in fact, the same length, and observing that if they were, he would have trisected angle A1OB1:

I could show you the trig to work out the actual arc lengths, but it's pretty ugly and probably not worth the effort. I'll just tell you they are not the same. Your construction is reminiscent of some attempts I've seen to trisect an angle. In particular, the figure looks much like Archimedes' method, which requires a marked straightedge, and that in itself is enough to tell me that the answer will be no. If the arcs were the same, then the angles would be in a 3:1 ratio (since they have the same arc length and the radii are in 3:1 ratio), and you would have trisected the angle; since I know that's impossible with a construction that can be done with compass and straightedge, I don't really have to do the extra work.

I tried to encourage him to do math, without the aim of trisecting an angle:

If that's what you're trying to do, don't feel it's foolish to try. As the alchemists discovered useful things in the process of trying to do the impossible, you may learn a lot about what does work in trying to do what won't. There are some fascinating ways to trisect an angle using special tools, as our FAQ tells you if you dig deep enough, ... and the attempt to prove that any given method might work can help you get a better feel for geometry, and stretch your mind considerably. What you'll want to do, though, is to develop the skills to prove for yourself whether something is true, rather than make a conjecture and have to ask whether it is true. That's the fun part of geometry, and what makes it more challenging than any other part of elementary math.

Hollis wrote to us periodically over the following years, sometimes with questions that I answered with comments like, “This looks suspiciously like an attempt to trisect an angle, which of course can’t be done (exactly) with compass and straightedge. Can you tell me what you are doing?” Eventually, he explicitly became a serial trisector, immune to whatever we tried to say.

The burden of proof

Here is a trisection attempt that turned out to be interesting:

Trisecting an Angle I've been looking for someone to talk to about the trisecting an angle problem from ancient Greece. I understand the whole modern algebra proof thing but it doesn't disprove the possibility of angle trisection. At least not from the way I have read it and understood it. I came up with a method when I was 16 and in geometry class and so far no one can disprove it. I tried proving it geometrically for a while but gave up. All I know is that with best drawing programs using only circles and unmeasured lines, it works at least to the naked eye for any angle from 5 to 175 degrees. I've done numerous examples trying to find one where it is off by more than the error when using a compass and so far everything I've done is a perfect trisection. Who can I show this to? I think I have something here...

Eric clearly doesn’t understand that algebra did prove that trisection (by the rules) is impossible; and that his attempt can’t be called exact until it is proved to be exact — the burden of proof is on him to prove it, not on others to disprove it! But I asked him to show his work, and (in a discussion too long to include here) discovered that it could be made exact if only you could adjust a center point so that other points coincide with a circle. This makes it like a marked-straightedge construction.

Unfortunately, this page got me started on a side career of making similar checks of approximate trisections.

Why your trisection isn’t valid

A 2001 question from Joe provided a perfect opportunity to discuss what people are misunderstanding when they think they have a trisection. It started innocently, as many do:

Angle Trisection: Construction vs. Drawing Has anyone ever divided an angle into three equal parts by construction? I have been told it has not been accomplished.

Note that Joe interprets the claim that it can’t be done as a mere challenge, that no one has yet done it. This is what drives trisection mania.

Doctor Tom replied:

Using the standard methods of construction with a straightedge and compass, it can be proven that it is impossible to trisect an arbitrary angle. People who think they have solved the problem usually make one of two mistakes: 1) They trisect a particular angle that happens to allow a trisection. For example, anyone can trisect a 90-degree angle. 2) They do not understand the "rules" of straightedge and compass construction. For example, if you are allowed to make two marks on the straightedge to turn it into a sort of ruler, you can trisect any angle. But the official rules do not allow this.

We have had a number of claims related to specific angles; here is one:

Trisecting a Right Angle

Others start with a known angle, such as Hollis’ 30°, just as an example, but apparently thinking that measuring their result as 10° will constitute proof.

But Joe turned out to be a serious trisector, as he replied:

I have trisected arbitrary angles up to 90 degrees. Don't laugh until you see it. Only a straightedge and a compass. No measuring. The drawing must be precise for the angle to be correct. Where could I submit my effort for confirmation?

So he claimed to satisfy the requirements, but something he said suggested the need to add another clarification, so I replied:

I notice something in what you just said that indicates where you are misunderstanding the trisection problem. Dr. Tom listed two mistakes people commonly make (trisecting only a specific angle, or using the wrong tools). But there is another that is even more common: not recognizing what we mean by an exact trisection. When you say that "the drawing must be precise," you show that it is the drawing itself that you have been focusing on. But to a mathematician, the drawing itself is nothing. It is only a representation of something that really happens in an ideal world where lines have no thickness, and so on. In that world, we can prove that a construction is ABSOLUTELY exact; either it meets the precise point you claim, or it is a false construction. And since this is the world of the mind, ONLY proofs count. It doesn't matter how good a drawing you make, it proves nothing.

Every trisector we have heard from has made a claim without proof, depending only on how things look. (Some, after reading this page, have made attempts at proof, but they generally have no idea what a real proof looks like; otherwise, they would have understood that what is proved impossible really can’t be done.) But no measurements of a physical drawing can be accurate enough; whereas when you do a proof, there is no need to have an accurate drawing.

So unless you can prove that your construction really works exactly, you have nothing to show anyone. And we know that you can't, because it has been PROVEN that such a construction can't be done. I've seen many constructions that come remarkably close, usually just because they are very complex; there is nothing at all impressive about a close approximation. Please don't waste your time on this, as so many people have.

Perseverance

Unfortunately, the discussion didn’t end here; the next month, Joe wrote back telling us about his constructions, each of which assumed something that is not true about chords and arcs (see below on that). And in 2004 he wrote again:

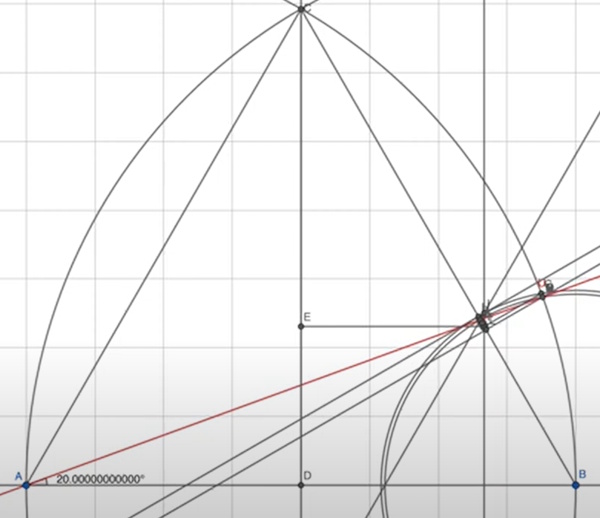

Trisecting an Angle Using Compass and Straightedge

There, he asked me to analyze his construction on Geometer’s Sketchpad (similar to the current GeoGebra), which I had used on Eric’s construction that I mentioned above; I had to tell him that not only physical measurements, but also calculations (necessarily rounded) by a program do not constitute proof. I did analyze it, to show him that it was not exact, but also demonstrated what a proof looks like, giving a proof of an angle bisection for comparison. At the end, I added, referring to the FAQ:

As that explains, it has been proved to be impossible to exactly trisect any arbitrary angle using only compass and unmarked straightedge; and as I pointed out, "exact" to a mathematician means something entirely different from "as close as you can measure"; it means "provably exact". "Impossible" is a common thing in math. For example, it is impossible to find two odd numbers whose sum is odd; it is easy to prove that the sum of two odd numbers is always even, so we just accept that. I've never heard of people who, when told this fact, spend their lives trying to find two odd numbers whose sum is odd; but there have been thousands of people who have wasted a lot of time trying to find a way to trisect an angle. Most of them probably have no idea that a valid trisection is not just a drawing but a proof! They just hear that it can't be done, don't understand how that could be proved, and decide to show that it doesn't apply to them. Since it's not as obvious as adding odd numbers, they never realize how silly what they are doing is. To keep your mind alert, I would suggest something more "constructive" than trying to do what has been proved impossible. Take some time to learn the basics of geometric construction and proof, then work through the exercises in a good book on the subject, which will ask you to do constructions that are hard but possible. That way you are giving yourself a major mental challenge, but one that you can really master with effort. It's a lot more rewarding!

I have said this sort of thing to several others I have corresponded with. This discussion continued a little further, and ended with his saying, “I will put your note about proof under the glass on my desk as a reminder to leave the trisect impossibility alone.”

But, alas, he wrote again in 2009, with yet another attempt. It turned out not to be close at all. He hadn’t learned a thing.

Trisecting a chord doesn’t trisect the angle

Let’s look at one more page: a proof that a common assumption of trisectors is false:

Trisecting an Angle and the Opposite Side in a Triangle Prove that it is impossible to have a triangle in which the trisectors of an angle also trisect the opposite side. I am unsure how to prove this. It seems that if i trisect the angles of an equilateral triangle so that each of the trisected angles is 20, it would indeed divide the opposite side into 3 equal pieces. I have completed geometry, and I have tried several things. I got started trying to use exterior angle theorem, but got confused. I think that may be a good way to do it, but I dead ended after extending two of the sides to create isosceles triangles. I think it may be all of the criss-crossing lines that is getting me confused.

I replied to this refreshing question:

I don't think I've ever tried proving this, but it's a very nice little theorem! It may seem as if trisecting an angle in an equilateral triangle would work, but it is not true. I think I'd approach it by contradiction. Suppose that you have a triangle ABC with trisectors BD and BE, D and E being on AC, and further suppose that D and E trisect AC, so that AD = DE = EC:Now focus on triangle ABE. Here BD bisects angle ABE, while D is the midpoint of AE; so BD is both an angle bisector and a median. What does that imply? Repeat with triangle DBC, and look for a contradiction. There may be many other ways to approach this, so if you see any ideas of your own while you try this out, go ahead and pursue them!

The implication I had in mind is that triangle ABE must be isosceles, because triangles ABD and EBD are congruent. It also implies that BD is perpendicular to AC. Since the same must be true of triangle DBC, this triangle can’t exist.

In summary, here is what I wrote to someone who wrote in 2009, starting out “Why do you print false information on your site?”:

It has been proved that you can't construct a provably exact trisection of an arbitrary angle using the classical rules (only a compass and unmarked straightedge, in a finite number of steps). People who claim they can, generally don't really have a provable trisection, or are bending the rules in some way without realizing it. ... If you have no proof to show me, then you have not met the requirements of a valid construction, and most likely it is just measurably close, not mathematically exact. The imprecision of physical tools has nothing to do with it, because we do not demonstrate the correctness of a construction by doing it physically and seeing that it looks as close as our tools can make it. The tools we really care about are all in the mind, and that is where the proof has to be done.

Pingback: Why Do We Need Proofs? – The Math Doctors

Oh dear! Whoever posted the response to the 7th grade math teacher did not fully understand Euclidean construction. First of all, he stated that a trisection is impossible. Some trisections are possible (a 90 degree angle) with Euclidean compass and straightedge, but some are not (a 60 degree angle). This is a rather trivial misstatement.

However, in the second paragraph, he stated that arbitrary points may be used in a construction. Wrong, wrong, wrong! The ONLY points that can be used in a Euclidean construction are given points and those points derived from previous steps of the construction. If arbitraty points could be selected, any construction would be possible.

See, for example, the discussion following Problem 8 of Problem Set 19.1 in

“Elementary Geometry from an Advanced Standpoint” by Dr. Edwin E. Moise, published by Addison-Wesley, 2nd printing 1964.

Michael E Ochs BA Mathematics

Univ of Colo

To your first comment, I have to say that one can’t give a complete statement every time one writes. “A trisection”, as explained later in the article, here means specifically a construction that is provably correct for any given angle. (Doctor Tom mentioned this further down, under “Why your trisection isn’t valid”.) That is, “a trisection” as used here means a general process, not a particular line one has drawn for a particular given angle.

I think it was reasonably clear that this was what the questioner intended (and a further conversation would have revealed if it wasn’t), so it was not necessary to define it fully at that point. But you are right that some people make that mistake, thinking that if they can construct a trisection of, say, a 90 degree angle, then they have proved the mathematicians’ claim wrong. That’s why this point was made several times later in the article. We do have to clearly define exactly what we mean by trisection.

Your argument about arbitrary points similarly needs clarification. What Doctor Tom said was, “The straight-edge can only connect points already constructed, or use arbitrary points“. I would argue that when you draw a line with a straightedge, you are drawing many “arbitrary points”! But that’s not your issue.

My initial expectation on reading your comment was that you might be referring to something like the axiom of choice; but when I found the book you refer to, it was talking about something that I think is really irrelevant here.

To quote, Moise says, “Strictly speaking, random choices of points are not allowed in doing construction problems. The reason is curious: if they were allowed, then the so-called “impossible construction problems” to be discussed later in this chapter would be not quite impossible. For example, an infinitely lucky person might manage to pick, at random, a point on a trisector of any given angle” [my emphasis].

But that would not really make “trisection” as we are discussing it possible; if you just happen to pick the right point, then your result is not provably correct, which is essential in any construction. I think he is to some extent making the same mistake you felt Doctor Tom was making, in supposing that all we mean by a construction is to draw a line that trisects some particular angle, on one particular occasion.

To be honest, I’m not sure what Doctor Tom meant by “use arbitrary points”; he might mean drawing an arbitrary point along the straightedge, or he might mean drawing a line through an arbitrary point. I don’t know whether he had a particular kind of construction in mind. But he definitely didn’t mean that you could draw a line at random and hope it would be the trisector you are looking for.

I agree that my first comment regarding “trisection” versus “a trisection” was probably too picky, and I withdraw it.

However, my comment regarding arbitrary point usage stands. Since the only two operations allowable in a Euclidean construction are:

a) use the straightedge to draw the line through two known points; or

b) use the compass to draw a circle with center at a known point and through a known point.

There is no operation that allows you to put your pencil anywhere else on the paper.

Regarding your statement about a drawn line containing infinitely many arbitrary points, you are correct. However, you know nothing about these points and may not use one of them in a construction until you have “located” one (wish I had a better word) via drawing a line or circle which intersects the line at the point in question. In addition, most of the points on the line have at least one coordinate that is a non-constructible number, and hence are not accessible vie construction.

Thanks for your patience.

Mike Ochs

Clearly there is a difference of opinion, probably based on different contexts.

In searching for references on this issue (on either side), I happened to run across this paper explaining constructions, by Tom Davis — who is, in fact, our Doctor Tom:

https://www.mathcircles.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/construct-1.pdf .

This gives us a better idea of what he is thinking, though it doesn’t show an example in which an arbitrary point plays a role. An important thing to note is that the target audience is advanced high school students doing constructions and exploring ideas like trisection, not mathematicians building a rigorous theory. (This is also why he allows setting a compass to a fixed radius and relegates the topic of the “collapsible compass” to a footnote.) I believe the context in which arbitrary points would be forbidden is the proof of impossible constructions, where arbitrary points are problematic as you have pointed out. In doing a construction, on the other hand, it seems perfectly natural to believe that we can choose any of the points we have already drawn in making a line.

Euclid himself did occasionally use an arbitrary point as part of a construction:

Euclid’s Elements, Proposition I.9

Here, instead of arbitrary point D, he could have used one of the given points; since Euclid didn’t use the concept of rays, but only segments with known endpoints, this would be possible. But if, in a modern context, we were only given a pair of rays, we would in fact have to pick an arbitrary point.

I also found the following book (Basic Algebra I, by Nathan Jacobson), which discusses how the concept can be fit into a rigorous treatment of constructible points:

https://books.google.com/books?id=JHFpv0tKiBAC&pg=PA216

Jacobson goes on to show how this does not interfere with his argument about constructible points.

I think that helps at least a little in reconciling Doctor Tom’s point of view for constructions in general with what is required in the proof of the impossibility of trisection. It was an interesting detail to look into, even though I don’t think it’s really relevant to anything else that was said.

Pingback: Compass and Straightedge: Why? – The Math Doctors

After putting 40-42 years’ efforts I have been able to trisect the following angles to unprecedent/miraculous approximation, that too, using only a compass and an unmarked straight edge with finite no. of quite easy steps…

30° to 10.000000°

36° to 12.000000°

40° to 13.333333°

45° to 14.999999°

54° to 17.999998°

60° to 19.999995° and so on…

The images the above are ready for uploading if some one want to see…..

It’s sad how many people waste their lives doing something that is utterly worthless; and how many who read an article like this fail to understand what we are saying, namely that mathematicians don’t care at all about such “approximate precision”. The only thing interesting about compass-and-straightedge constructions (beyond a few basic ones that might be useful to carpenters) is whether they can be proved to be absolutely exact, in theory.

To quote what I said above, “I’ve seen many constructions that come remarkably close, usually just because they are very complex; there is nothing at all impressive about a close approximation. Please don’t waste your time on this, as so many people have.”

I can only assume you never actually read this.

In a recent discussion, reader Bernard asked for clarification of the overall issue here. I think what Doctor Rick said is worth posting:

What is impossible is, given an arbitrary angle, to construct an angle whose measure is exactly one-third of that of the given angle, using an (ideal) compass and unmarked straight-edge. Use of those tools corresponds to application of theorems of Euclidean geometry, by means of which the construction (if it could be done) would be proved to be exact.

What is possible is a means of constructing an angle whose measure is approximately one-third of that of the given angle, accurate to some specified maximum error. Such an algorithm might be repeated as often as necessary to attain any desired level of accuracy, short of exactness.

These are two separate problems. We do not want students to be confused; we want it to be clear that solving the second problem is not a great challenge and so not of interest mathematically, but that the first problem has been proved to be absolutely impossible. What’s of mathematical interest is not any attempt to solve the first problem (which would be futile), but rather the proof of impossibility. The latter has been accomplished, and involves some pretty deep and beautiful mathematics.

Here’s a mind-blowing Euclidean construction, part of which is microscopic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KxMbk9z18yg

Hi, Paul.

I’ll assume you did not create this video and are not supporting it, since, having read my discussion here, you presumably understand that it is not really a valid trisection, and is therefore worthless.

The description says this:

As you know from reading this page, “accurate” in math is different from “exact”. The latter does not mean that “any error is microscopic”; it means that there is no error at all. And “proof” in math does not mean “demonstrating by measurement”, it means using theorems to prove that the claim is necessarily true. Since what we call “impossible” is an exact trisection, rather than just an “accurate” one, all this work has accomplished exactly nothing; it is not impressive at all, except as a demonstration of how far people can go in wasting their time.

The page quotes Grok AI, which is rather diplomatic in its evaluation, as if trying to encourage a child:

The truth is, there is no “potential” here.

In the old days, people would spend a lot of time making careful drawings to “prove” that their construction was as accurate as they could measure; now computers allow us to waste even more effort to make a drawing that (merely by virtue of its complexity) is far more “accurate”, and yet still utterly meaningless. They can even get AI to say nice things about their work, which is also meaningless, since AI is programmed to convince you that it is smart, rather than to actually be smart.

Please reread my most recent comment, which applies here.

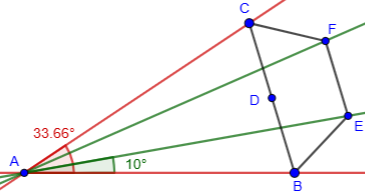

Interesting discussions that lead up to this inquiery. What is wrong about this trisection procedure in Euclidian terms?

“Let two crossing lines be the sides of two unequal opposing isosecles trangles with a common vertex. Construct a semihexagon over the base of each triangle facing away from the vertex. Connecting lines from the corners of the hexagons pass through the vertex, thereby trisecting the vertex angle of the triangles”

Hi, Hans.

There are two main things wrong: It is not clearly described, and you have not given a proof that you have trisected the angle. Both are necessary, as we’ve explained here, for claiming a trisection.

But also, if I have correctly interpreted your description, it just doesn’t work:

My main uncertainty about your description is the word “unequal”.