A question came in just this month, closely related to the last question in the post When Is an Improper Integral Not an Improper Integral? last April. There, we considered an integral where substitution led to a new integral with limits from 0 to 0, and after some discussion we decided that, while odd, the answer was valid. But I had a sense that something was not quite right, and that sometimes the method used there would fail. Here we get to see that happen – and then fix it.

A substitution that works too quickly

The question, like many thought-provoking questions we get, is from Amia:

Hi Dr math,

I have this question:

How do I integrate (4x^3+6x^2+2x)^3. (x^2+x)^5 from -1 to 0?

If I suppose u = x^2 + x, then the interval becomes 0 to 0.

And without carrying out the integration, the answer is zero.

What is your opinion?

Thank you in advance.

The problem is to integrate this definite integral: $$\int_{-1}^0(4x^3+6x^2+2x)^3(x^2+x)^5dx$$

Amia has made the substitution $$u=x^2+x\\du=(2x+1)dx\\dx=\frac{du}{2x+1}\\x=-1\rightarrow u=0\\x=0\rightarrow u=0$$ So the new integral will be, without bothering with the details of the integrand, $$\int_0^0(\text{something in }u)^3u^5\frac{du}{\text{something else in }u}$$ Is that enough to convince ourselves that the integral is zero? Or might something go wrong in the work we haven’t done?

I answered:

Hi, Amia.

The answer is, indeed, 0, though I would want to do a little more to make sure it’s sensible. It happens that I’m currently working on a post on a question you had with a related issue (involving ∫x f(sin x)dx), and also revisiting a previous post based on other questions with the same issue (what I called a “vanishing interval”), namely When Is an Improper Integral Not an Improper Integral?

One point I’ll be making is that you need to actually carry out the substitution, rather than just look at the limits of integration, to see that it really works. (Otherwise, couldn’t you just claim to be making the same substitution in any integral with these limits, and say the answer is zero?)

Did you do that?

The post I was working on will be the next post.

To carry out the substitution, we need to actually express everything in terms of u, as I didn’t do (with good reason) above.

But it doesn’t look like the work would be easy, so I tried another approach.

First I factored the integrand and found that the first part is a power of 2x(x+1)(2x+1), which is very convenient. At first I was thinking that the fact that 2x+1 is the derivative of x2+x = x(x+1) would make it a good substitution, but it’s not quite that simple.

I had imagined solving for x as a function of u and plugging that into \((4x^3+6x^2+2x)^3\), which would be horrendous. But factoring made things a little simpler: The integrand \((4x^3+6x^2+2x)^3(x^2+x)^5\) becomes \((2x(x+1)(2x+1))^3(x(x+1))^5\), and \(2x(x+1)(2x+1)=2uu’\); but raising the derivative to a power will mess things up! So there’s a remarkably close relationship, but not a helpful one (yet).

But we can actually do it!

What we would really need to do is to express \(4x^3+6x^2+2x\) in terms of u, which requires the inverse of \(u=x^2+x\), that is, solving it for x. But this is not one-to-one (an issue that also arose in the past post); the best we could do is $$x=\frac{-1\pm\sqrt{1+4u}}{2},$$ where we have to take a different sign in different parts of the interval. My first thought was that this would be very ugly, so I didn’t pursue it at the time; but now that I look at it, it’s not really as bad as I imagined.

First, my “something else in u” in the denominator turns out to be \(2x+1=\pm\sqrt{1+4u}\); and “something in u” on top is \(4x^3+6x^2+2x=(x^2+x)(2x+1)=\pm u\sqrt{1+4u}\). So the integral becomes

$$\int_0^0\left(\pm u\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^3u^5\frac{du}{\pm\sqrt{1+4u}}\\=\int_0^0u^8\left(\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^2du=\int_0^0u^8\left(1+4u\right)du\\=\int_0^0\left(u^8+4u^9\right)du=\left[\frac{1}{9}u^9+\frac{2}{5}u^{10}\right]_0^0=0$$

So the plus-or-minus (that is, the lack of a single inverse) is not an issue, because it cancels out, and we can trust the answer.

But let’s be more cautious, and split the integral into two parts, so we can use the appropriate inverse in each:

$$\int_0^{-1/4}\left(-u\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^3u^5\frac{du}{-\sqrt{1+4u}}+\int_{-1/4}^0\left(+u\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^3u^5\frac{du}{+\sqrt{1+4u}}\\

=\int_0^{-1/4}u^8\left(\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^2du+\int_{-1/4}^0u^8\left(\sqrt{1+4u}\right)^2du\\

=\int_0^{-1/4}u^8\left(1+4u\right)du+\int_{-1/4}^0u^8\left(1+4u\right)du\\

=\int_0^{-1/4}\left(u^8+4u^9\right)du+\int_{-1/4}^0\left(u^8+4u^9\right)du\\

=\left[\frac{1}{9}u^9+\frac{2}{5}u^{10}\right]_0^{-1/4}+\left[\frac{1}{9}u^9+\frac{2}{5}u^{10}\right]_{-1/4}^0=0$$

So the substitution does work when we carry out all the details.

Using symmetry instead

But doing just part of that made me aware of another possibility (which may well be the intended approach for the problem):

But then I noticed that your substitution is not one-to-one (which will be a central issue in my coming post), and is symmetrical about x = -1/2. Knowing that symmetry can be important in problems like this (and is often the reason for the result being zero — this should sound familiar from the past questions), I considered making a substitution that shifts the integrand so that x = -1/2 moves to 0. That is, we could let u = x + 1/2, though for simplicity instead I let u = 2x+1.

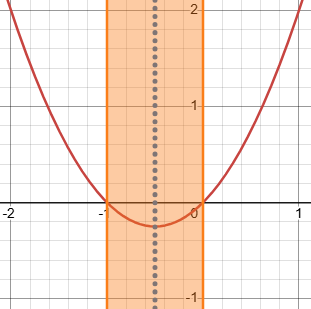

Here is a graph of the substitution (x horizontal, u vertical) showing the symmetry:

I’ve shown the interval over which we are integrating, which has the same symmetry. Interesting …

(It was probably the fact that the derivative is \(u’=2x+1\), which is zero at \(x=-\frac{1}{2}\), that led me to notice the symmetry, and how well it fit with other things.)

But in fact the integrand itself has a related symmetry, because its factors are all \(x^2+x\) and \(2x+1\). In this case, it is a symmetry around the point \(\left(-\frac{1}{2},0\right)\):

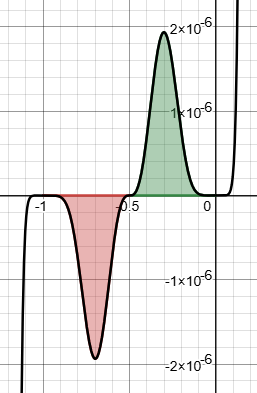

Incidentally, here is the graph of the integrand, where you can see its symmetry:

Try that. What you’ll find is that the new integrand is odd, and the new limits of integration are symmetrical about 0, which will result in the answer being zero, without needing further work..

Just from the graph, we can see that the negative area (red) and the positive area (green) will cancel out, so the integral is 0.

We don’t need the graph to show that; the substitution I suggested takes care of it. Since we won’t be seeing Amia’s work on it, let’s do it here:

First, by factoring, $$\int_{-1}^0(4x^3+6x^2+2x)^3(x^2+x)^5dx=\\\int_{-1}^0(2x(x+1)(2x+1))^3(x(x+1))^5dx=\\\int_{-1}^0 8x^8(x+1)^8(2x+1)^3dx$$

Letting $$u=2x+1\\x=\frac{u-1}{2}\\du=2dx\\x=-1\rightarrow u=-1\\x=0\rightarrow u=1,$$ the integral becomes $$ \int_{-1}^{1}4\left(\frac{u-1}{2}\right)^8\left(\frac{u+1}{2}\right)^8u^3du=\int_{-1}^{1}4\left(\frac{u^2-1}{4}\right)^8u^3du$$

Now we can just observe that we are integrating an odd function over a symmetrical interval, so the integral is zero.

But is it necessary to do all that?

Amia responded:

Thank you, Dr Peterson,

I think here the integrand is polynomial, so it’s not necessary to calculate the integral.

I was not sure how to interpret that, but it led me in an interesting direction:

I’m not sure what you are saying here.

Of course, the problem tells you to calculate the integral; I suppose you mean that you don’t need to carry out all the work, as I said you must, because some theorem tells you it will not be necessary. What theorem is that?

The integrand being a polynomial implies it is integrable, but I don’t see how it ensures that the substitution would be successful if you did it.

The fact is (as I mentioned near the end of my recent answer) that the official theorems for integration by substitution actually require a one-to-one function (even though many textbooks don’t mention it, and we therefore said it is not required). So those theorems do not allow what you are doing; you need to do more to show it is correct. Moreover, even if the substitution does not have to be one-to-one, you have to be very careful when it is not; odd things can happen. That’s what I’m learning as I explore this issue.

This claim that the substitution must be one-to-one came from a discussion I’d reported with ChatGPT, which appeared to give valid references; but I have since realized that this was in part a hallucination; a couple sources do include that in their theorems, but in fact we rather commonly use non-injective (not one-to-one) substitutions. We just need to be careful (as I will be as we move forward). This will be discussed further in the next post.

But let’s test your claim, as I interpret it, that as long as the integrand is a polynomial, what you did is all that is needed. (I’m very curious to see what will happen, myself.) I’ll make up a problem that looks like yours, but simpler.

Suppose we want to integrate, say ∫-10 2x dx, using the substitution u = x2 + x.

You seem to be saying that, because the integrand, 2x, is a polynomial, and the new limits of integration are 0 and 0, therefore the integral is 0. You don’t bother to actually do the integration, because you are confident of this. Am I right about this?

Normally, we use a substitution that has connection to the integrand, namely an “inner function” whose derivative is also present. This would be a preposterous substitution to attempt! But the claim (as I chose to take it) was that it would work for any polynomial, and it might be fun to try!

Of course, the truth is that ∫-102x dx = [x2]-10 = 0 – 1 = -1, not 0. So the claim is wrong.

I intentionally chose a very simple integrand, and one that did not have the symmetry of our original problem, with this goal in mind. Can we actually use the substitution and get the right answer?

A preposterous substitution in a simple integral

Now let’s actually do the work with the substitution (which will not be straightforward!), to see what happens:

We are letting

\(\displaystyle u=x^2+x\)

\(\displaystyle du=(2x+1)dx\); \(dx=\frac{du}{2x+1}\)

\(\displaystyle x=\frac{-1\pm\sqrt{1+4u}}{2}\) (applying the quadratic formula to \(x^2+x-u=0\))

We don’t have the usual sort of simple replacement of one expression by another, as 2x+1 doesn’t appear in the integrand. So we have to do it the hard way.

Here there are two values for x, as we’ve seen, because u is not a one-to-one function of x.

In particular, since u is not a one-to-one function of x, we can’t just replace x in the integrand with one expression; we will use one inverse when x < -1/2, and another when x > -1/2. So we can split the definite integral into two parts:

\(\displaystyle\int_{-1}^0 2xdx=\int_{-1}^{-1/2} 2xdx+\int_{-1/2}^0 2xdx\)

The first integral uses \(\displaystyle x=\frac{-1-\sqrt{1+4u}}{2}\):

\(\displaystyle\int_{-1}^{-1/2} 2xdx

=\int_{0}^{-1/4}\left(-1-\sqrt{1+4u}\right)\frac{du}{\left(-1-\sqrt{1+4u}\right)+1}\\

\displaystyle=\int_{0}^{-1/4}\left(-1-\sqrt{1+4u}\right)\frac{du}{-\sqrt{1+4u}}\\

\displaystyle=\int_{0}^{-1/4}\left((1+4u)^{-1/2}+1\right)du\\

\displaystyle=\left[\frac{1}{2}(1+4u)^{1/2}+u\right]_{0}^{-1/4}\\

\displaystyle=\left[\frac{1}{2}(0)^{1/2}-\frac{1}{4}\right]-\left[\frac{1}{2}(1)^{1/2}+0\right]\\

\displaystyle=-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{1}{2}=-\frac{3}{4}\)The second integral uses \(\displaystyle x=\frac{-1+\sqrt{1+4u}}{2}\):

\(\displaystyle\int_{-1/2}^0 2xdx

\displaystyle=\int_{-1/4}^0\left(-1+\sqrt{1+4u}\right)\frac{du}{\left(-1+\sqrt{1+4u}\right)+1}\\

\displaystyle=\int_{-1/4}^0\left(-1+\sqrt{1+4u}\right)\frac{du}{\sqrt{1+4u}}\\

\displaystyle=\int_{-1/4}^0\left(-(1+4u)^{-1/2}+1\right)du\\

\displaystyle=\left[-\frac{1}{2}(1+4u)^{1/2}+u\right]_{-1/4}^0\\

\displaystyle=\left[-\frac{1}{2}(1)^{1/2}+0\right]-\left[-\frac{1}{2}(0)^{1/2}-\frac{1}{4}\right]\\

\displaystyle=-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{4}=-\frac{1}{4}\)Therefore

\(\displaystyle\int_{-1}^0 2xdx=\int_{-1}^{-1/2} 2xdx+\int_{-1/2}^0 2xdx=-\frac{3}{4}-\frac{1}{4}=-1\)

This is the correct answer. We had to carry out the details of the substitution in order to obtain it. We couldn’t just look at the limits of integration and say the answer was zero!

And when you look at the details, you sometimes see a need to split the integral – but not always.

I still have to think more about what is happening here, and how it relates to other questions of this sort. The main idea is that u goes from 0 to -1/4 and from -1/4 to 0, but it behaves differently in each direction, so it doesn’t cancel out as it did in some other problems we’ve looked at.

Another example of a failed substitution

As another example (suggested by ChatGPT), consider $$\int_0^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx,$$ using the substitution $$u = \cos(x)\\du = -\sin x dx\\x=0\rightarrow1\\x=2\pi\rightarrow1$$

On the surface, this seems reasonable, though we notice that the substitution is not one-to-one. The transformed limits lead us to think that the integral is, once again, 0.

But this integral would normally be done using a power-reduction formula: $$\int_0^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx=\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1+\cos(2x) }{2}dx=\left[\frac{2x+\sin(2x) }{4}\right]_0^{2\pi}\\=\left[\frac{4\pi+\sin(4\pi) }{4}\right]-\left[\frac{0+\sin(0) }{4}\right]=\pi$$

So what is going wrong? Again, let’s carry out all the work, paying close attention.

This is another of those integrals that are not set up to make the substitution natural, because the differential is not there. Instead, we have to construct the differential.

We might write $$dx=\frac{du}{-\sin(x)}=\frac{du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}},$$ so the integral becomes $$\int_0^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx=\int_1^1 \frac{u^2 du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}}.$$

But it is not always true that \(\sin(x)=\sqrt{1-\cos^2(x)}=\sqrt{1-u^2}\). That is true only when the sine is positive, in the interval \(\left[0,\pi\right]\). So we could use this if the limits were 0 to π, but not as it is. (Note that this happens to be exactly an interval where the substitution is one-to-one! It’s actually a manifestation of an alternative inverse.)

Using the appropriate sign in each interval, we get $$\int_0^{2\pi}\cos^2(x) dx\\=\int_0^{\pi} \cos^2(x) dx+\int_{\pi}^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx\\=\int_1^{-1}\frac{u^2 du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}}+\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}+\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=2\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$$

Now, how shall we integrate that? I would use a trig substitution; but that essentially takes us back to the original problem: $$u=\sin(\theta)\\\theta=\arcsin(u)\\\cos(\theta)=\sqrt{1-u^2}\\du=\cos(\theta)\\u=-1\rightarrow\theta=-\frac{\pi}{2}\\u=1\rightarrow\theta=\frac{\pi}{2}$$ so the integral becomes $$2\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}=2\int_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^\frac{\pi}{2}\frac{\sin^2(\theta)\cos(\theta)d\theta}{\cos(\theta)}\\=2\int_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^\frac{\pi}{2}\sin^2(\theta)d\theta$$

What’s changed is that we have new limits, corresponding to only half of the original interval, And when we use the power-reduction formula (having learned our lesson), we get

$$2\int_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^\frac{\pi}{2}\sin^2(\theta)d\theta\\

=2\int_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^\frac{\pi}{2}\frac{1-\cos(2\theta)}{2}d\theta\\

=2\left[\frac{2\theta-\sin(2\theta)}{4}\right]_{-\frac{\pi}{2}}^\frac{\pi}{2}\\

=2\left[\frac{\pi-\sin(\pi) }{4}\right]+2\left[\frac{-\pi-\sin(-\pi)}{4}\right]=\pi$$

So by being careful, we avoided the errors that arose from different behavior over different subintervals in the original variable – which were hidden by the appearance that there was no interval at all in the new variable.

By the way, we have a leftover question: Is it legal to make a substitution that is not one-to-one? Absolutely, as long as you are careful. In fact, when I checked one of my textbooks (Larson/Hostetler/Edwards), I noticed that the first exercise of a definite integral solved by substitution is $$\int_{-1}^1x\left(x^2+1\right)^3dx,$$ which clearly is to be solved using the non-injective function $$u=x^2+1\\du=2xdx\\x=-1\rightarrow u=2\\x=1\rightarrow u=2$$ It’s exactly the type we’ve looked at here, giving an answer of 0 because the two limits are the same! (The book had used \(\int_{0}^1x\left(x^2+1\right)^3dx\), with different limits, as the first example of the method.)

Pingback: Another Tricky Integration by Substitution – The Math Doctors