Last time, we looked at a problem that had a fairly easy solution, but I had to convince myself that the situation it assumed was actually possible, because the work did not imply its existence, but merely assumed it. Here I want to show several examples of what I feared: problems where a perfectly good method of solution is applied to inconsistent premises, leading to an apparently valid answer that doesn’t really exist at all. I call such a solution “vacuous”, in the sense that a statement can be vacuously true because what it refers to doesn’t exist. (Technically, though, any answer to such a problem is vacuously true; here we’re talking about good reasoning for a bad problem.) This happens more often than you might think!

Area of an impossible triangle

We’ll start with a recent question, from Amia in early November:

Hi Dr Math,

I have the question below and my solution

Given a right-angled triangle.

The hypotenuse is 10, and the altitude to the hypotenuse is 6.

Find its area.Area = 0.5 (10)(6) = 30.

Is it ok? Or the dimensions are not correct?

The work is appropriate, given the data: The area of a triangle is half the product of the base and the altitude (to that base), so $$A=\frac{1}{2}bh=\frac{1}{2}(10)(6)=30$$

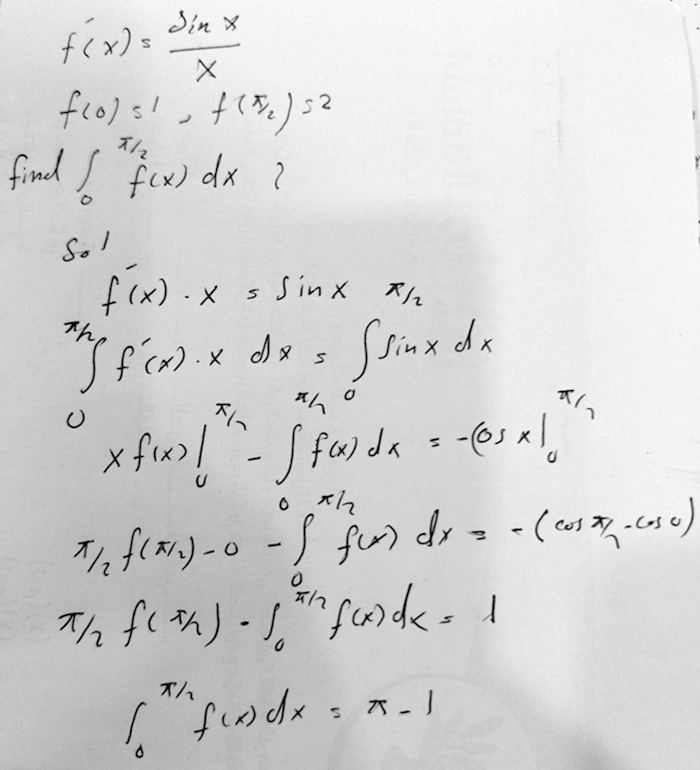

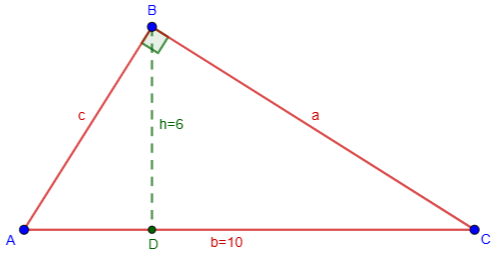

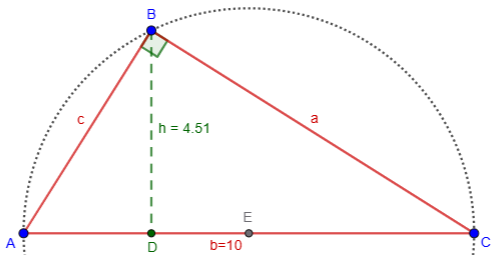

But we’re given an extra piece of information that we didn’t use: It’s a right triangle. So an initial (not necessarily accurate) sketch of the problem would look like this:

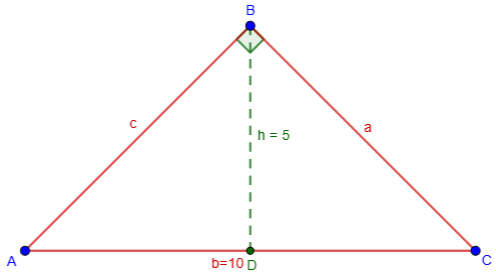

But when I made this drawing on GeoGebra, the actual length of BD as drawn is 4.51, not 6; and in fact, no matter where I place B, while maintaining a right angle, I can’t make it any larger than 5:

That is because, to construct a right triangle with a given hypotenuse, we can construct the circle with that segment as diameter, and choose any point B on the circle:

This point can’t be any further from the hypotenuse than the radius of the circle.

So the triangle as described does not exist.

I answered:

You are right to wonder if the triangle specified actually exists. I have long been interested in problems asking what would be true under some conditions, but for which we don’t know whether the conditions are consistent. I think of the solution to such a problem as vacuous, as it would be valid if a non-existent object existed – but it does not!

In this case, you can solve the triangle and show that x and y turn out to be imaginary, so in fact this triangle does not exist; or you can use the fact that the greatest possible altitude to a given hypotenuse c is c/2. (This follows from the fact that the other vertex must lie on a circle whose diameter is the hypotenuse.) So in this problem, since the altitude to the hypotenuse is greater than 5, the triangle does not exist.

The correct answer is that the triangle does not exist, and so does not have an area!

Did you try constructing the triangle and find that you couldn’t do it, or did you just recognize that existence needed to be demonstrated rather than assumed?

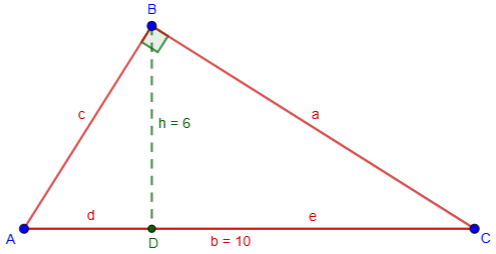

Let’s solve the triangle. We are given that angle B is a right angle, \(b=AC=10\), and \(h=BD=6\).

The right triangle tells us that $$a^2+c^2=100.$$ (I apologize for the non-standard labeling, but I had to use b for the base, even though the hypotenuse is usually called c!)

The altitude forms two smaller right triangles, which tell us that $$d^2+36=c^2\\e^2+36=a^2.$$

Also, $$d+e=10.$$

Collecting variables on the left, we have a system of equations: $$\eqalign{[1]&a^2+c^2&=100\\ [2]&c^2-d^2&=36\\ [3]&a^2-e^2&=36\\ [4]&d+e&=10}$$

Subtracting [1] – [2], $$a^2+d^2=64;$$ subtracting [3] from this, $$d^2+e^2=28;$$ squaring [4] and subtracting the last equation, $$2de=72$$ so \(de=36\).

Combining this with [4], we find that $$d=5+i\sqrt{11}\\e=5-i\sqrt{11},$$ or vice versa.

Therefore, $$a^2=e^2+36=50-10i\sqrt{11}\\c^2=d^2+36=50+2i\sqrt{11},$$ so \(a\approx7.4162-2.2361i\) and \(c\approx7.4162-2.2361i\). The complex numbers mean this triangle doesn’t exist.

In this problem, the issue turned out to be inconsistent data. If the height had been given as less than 5 (or if we weren’t told it’s a right triangle), the problem would have been valid, and our answer would have been correct. So the ultimate problem is that if we failed to check for consistency, we would be convinced of an invalid answer. And what if it were harder (or even impossible) to do such a check? We might never know!

Probability of an impossible event

At work a few days before that, I had been called over by a fellow tutor working with a student who had been given a simple problem:

Given that P(A) = 0.8, P(B) = 0.4, and P(A ∩ B) = 0.5, find P(A ∪ B).

This can be solved easily using the formula $$P(A\cup B)=P(A)+P(B)-P(A\cap B)$$ We find that $$P(A\cup B)=P(A)+P(B)-P(A\cap B)=0.8+0.4-0.5=0.7$$

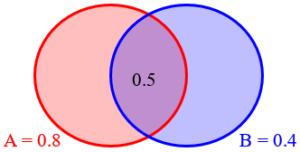

That seems perfectly reasonable. But someone (probably the tutor trying to help the student see where this formula comes from) tried drawing a Venn diagram to show what was happening:

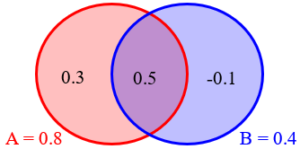

To find the probability of the union without using the formula, we can just fill in the missing spots (by subtraction) and add them up:

Oops! Because the probability of the intersection is greater than the probability of B itself, the probability of the rest of B turns out to be negative. This is, of course, impossible!

On the other hand, it is true that \(0.3+0.5-0.1=0.7, so the answer we got is “correct” in some sense.

So although we had no trouble finding the answer to the question, the question, again, is invalid.

The other tutor wanted my opinion on how to answer this problem. Is 0.7 an acceptable answer, or should the student reject the problem?

I asked ChatGPT about this problem, in the course of a discussion of the sort of problems we’re discussing here, and it concluded with this:

A very safe test answer—appropriate almost anywhere—is:

“Using inclusion–exclusion, P. However, the given probabilities are inconsistent since , so no such probability space exists.”

That answer is never wrong and often earns maximal credit.

I doubt that the problem was intended to illustrate this issue; more likely it was just designed without careful thought. There are some kinds of problems that can be written at random; others have to be designed starting with the intended solution in order to avoid making the work difficult or ugly, though the problem would still be valid; and there are others, like this, must be planned carefully in order to be valid at all! But that is easy to overlook, both as a teacher and as a student.

Evaluating an expression with impossible values

A classic kind of problem where I am often concerned that the problem may be vacuous was discussed in Finding a Symmetric Polynomial Given Others. (which is rather like the problems last time, both using elegant shortcuts that directly use the given, bypassing questions of existence). There we were given the values of two or more expressions in one or more variables, and have to find the value of another expression. Often it is difficult, if not impossible, to solve for the actual values of the variables, but by manipulating the expressions, we can find the answer anyway. But what if there are no values of the variables for which the given conditions hold? In each example there, I showed that that does not happen (as long as you allow for complex numbers). I have a feeling I have seen one of these that was vacuous, but I don’t have a record of such a problem. It may be that I am thinking of problems where we expect the values to be real numbers, but our work doesn’t tell us whether that can be true.

Here is an example of that sort that I’ve made up:

The perimeter of a rectangle is 8 meters, and the length of its diagonal is 2 meters. What is the sum of the reciprocals of the length and width?

The givens imply these equations, where the length and width are x and y: $$x+y=4\\x^2+y^2=4$$ We want to find $$\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}=z$$

Following the technique shown in the page I referred to, we first observe that $$z=\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{y}=\frac{x+y}{xy}$$ We know the value of \(x+y\); can we find the value of \(xy\)?

/Squaring the first equation, $$(x+y)^2=16\\x^2+2xy+y^2=16\\xy=\frac{16-(x^2+y^2)}{2}=\frac{16-4}{2}=6$$

Therefore, the answer is $$z=\frac{x+y}{xy}=\frac{4}{6}=\frac{2}{3}$$

But if we try to work it out directly (by actually finding x and y), we get the equation $$x+\frac{6}{x}=4,$$ leading to $$x^2-4x+6=0$$ and $$x=\frac{4\pm\sqrt{-8}}{2}=2\pm i\sqrt{2}$$ So there is no such rectangle; the sides would be complex numbers. Yet we were able to find the sum of the reciprocals without discovering that.

And, in fact, the reciprocals are \(\frac{1}{2+ i\sqrt{2}}=\frac{2- i\sqrt{2}}{6}\) and \(\frac{1}{2- i\sqrt{2}}=\frac{2+ i\sqrt{2}}{6}\), whose sum is \(\frac{2}{3}\). just as we said. If the rectangle existed, our answer would be right. But it doesn’t, so the answer is vacuous. (Of course, if I hadn’t said x and y were sides of a rectangle, the answer would be perfectly valid.)

Acceleration at an impossible moment

Here’s a calculus problem from Amia in September, 2024:

Hi Dr math,

I want to check the validity (truth) of this question.

If a position function of a body moving in a straight line is given by

x(t) = 3 sin 3t + 4 cos 3t ,

what is the acceleration of the body when x = 10?

Solution:

I think the question is wrong because x(t) will never be 10.

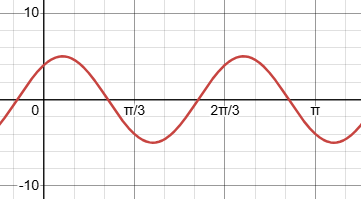

Here is a graph of x as a function of t, showing that x never reaches 10:

We don’t yet have a vacuous solution, because he didn’t find a solution without noticing the error, as in the other examples. But we can do so, by finding the velocity (first derivative) and acceleration (second derivative) without first solving for t: $$\eqalign{x&=3\sin(3t)+4\cos(3t)\\v&=\frac{dx}{dt}=9\cos(3t)-12\sin(3t)\\a&=\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}=-27\sin(3t)-36\cos(3t)\\&=-9(3\sin(3t)+4\cos(3t))=-9x=-9(10)=-90}$$ That’s the vacuous solution: We have an answer, without having seen any evidence that it is impossible!

Doctor Rick answered, having noticed this:

You are correct: x(t) cannot equal 10. Even if the arguments of sin and cos were different, so that the phase relationship between the two terms could vary, the maximum x could not be greater than 3(1) + 4(1) = 7.

Perhaps this error came about because the writer of the problem used a short-cut: since x(t) is a sinusoid of the form x(t) = A sin(3t + φ), its second derivative is –9x(t). We don’t need to determine the value of A or φ, so the writer may not have thought to check whether A ≥ 10 for this function.

The greatest possible value of x, in principle, would occur if the two sinusoids being added were (at least momentarily) in phase, so that each had its maximum value of 1 at the same time.

Our function simplifies to $$\eqalign{x&=3\sin(3t)+4\cos(3t)\\&=5\left[\frac{3}{5}\sin(3t)+\frac{4}{5}\cos(3t)\right]\\&=5\left[\cos(\varphi)\sin(3t)+\sin(\varphi)\cos(3t)\right]\\&=5\sin(3t+\varphi)}$$ where \(\varphi=\arctan\left(\frac{4}{3}\right)\). That explains the form he mentions, demonstrating that the actual maximum is 5, as in the graph.

I added,

Of course, it is also conceivable that the problem is intended to see whether you will notice this issue! The correct answer is, “That will never happen”. In that sense, it’s a valid question. And many real-life problems have such an answer.

My sense is that too many students, and perhaps their teachers, think of math as a game in which trick solutions are better than working through details. But knowing whether something will actually happen is important in real life. Imaging designing a flight to Mars and making sure you will have exactly the right amount of fuel when you land, but not noticing that you won’t actually get there at all!

Amia replied,

Using logic,

A false argument will lead to a false conclusion.

If a false then b is false ( I don’t know what is the name of this role).

This is not quite true; you can obtain a correct answer by wrong reasoning. But what he said reminded me of a relevant concept in logic. I responded,

You may be thinking of what we call “vacuous truth“. If something never happens, then anything we say about it can be considered true. (All Martian kangaroos are pink? Yes, because there are no kangaroos on Mars that are not pink.) So I suppose you could argue that any answer you gave for the acceleration when x=10 would technically be correct.

But I think a better answer here is to explicitly say that the condition of the question is impossible. If someone asked me what color my Martian kangaroo is, I would not say “pink”, but rather, “I don’t have any kangaroos.”

Somewhat similarly, the best answer to “When did you stop beating your wife?” is “I never did beat my wife.” You need to escape from the expected set of answers.

This is the source of my calling these “vacuous problems”.

This is also one of many reasons I don’t like multiple-choice problems. Sometimes the right answer is not one of the choices! Here, if the choices included \(-90\), but not “that never happens”, then you would be stuck.

Solving an inconsistent integral problem

We’ll close with a question, again from Amia, from last May:

Hi Dr Math,

I want to check if the question has no error?

If \(f'(x)=\frac{\sin(x)}{x}\), \(f(0)=1\), and \(f\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=2\), then \(\int_0^{\frac{\pi}{2}}f(x)dx=\)

(a) \(\pi\), (b) \(1-\pi\), (c) \(\pi-1\), (d) \(-\pi\)

I can see it’s not defined at zero for f'(x).

My solution:

The work nicely uses integration by parts; Amia’s specific question is whether the fact that \(f'(x)=\frac{\sin(x)}{x}\) is undefined at \(x=0\) (because it has the form \(\frac{0}{0}\)) makes it invalid to integrate it.

I answered:

Hi, Amia.

This is a very interesting question, and an interesting solution; but it is invalid for a different reason than you think.

The fact that the integrand is not technically defined at x = 0 is not a problem; as we’ve discussed before, the value at one point has no effect on the integral, and we can define f'(0) = 1 to make it continuous.

One such discussion is found in When Is an Improper Integral Not an Improper Integral? Since changing the value of a function at one point has no effect on its integral, we can “fill the hole” with no trouble.

As is my habit when I have time (due to the sort of issues we’ve seen above), I had checked the givens in the problem to see if they made sense, and found a problem:

But there is another issue!

Given f'(x), we can (in principle, though not using elementary functions) find f(x), which will be

f(x) = f(0) + ∫0x f'(t) dt = 1 + ∫0x sin(t)/t dt

But this is enough to determine the value of f(π/2). If that value is not 2, then the problem is invalid!

And in fact, according to Wolfram Alpha,

so we have f(π/2) ≈ 2.37076.

The problem presumably gave a value for this integral (in saying that \(f\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)=2\)) because (a) the author knew the student would not be able to work out an actual value for it, and (b) they thought it was arbitrary, and not implied by the rest of the problem. As a result, Amia’s solution (which is quite likely what they expected) accidentally became vacuous. It assumed the given value, whereas I have found it directly, and found the given value to be wrong.

The function Si (the “sine integral”) is mentioned in Integration: Sometimes It Just Can’t Be Done!

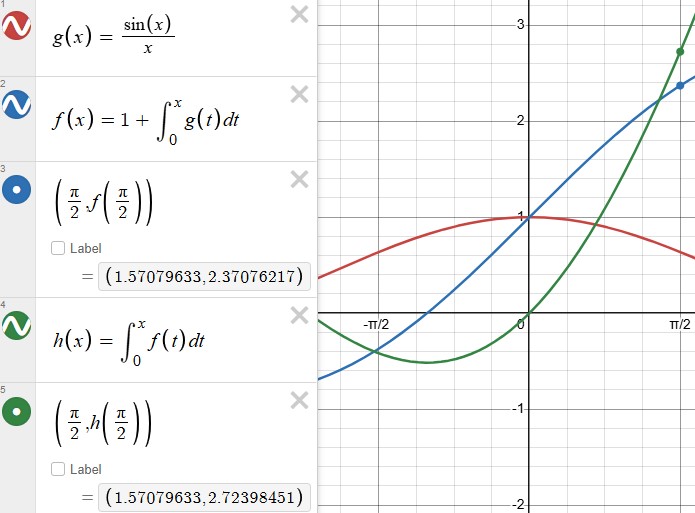

Here I have graphed f'(x) and f(x) on Desmos:

The red curve is f ‘(x), which you can see is continuous at x = 0; blue is f(x), which has the correct value at x = 0 but the wrong value at x = π/2; and green is the integral you are asked for. So, if we remove the wrong value given for f(π/2) from the problem, the answer to the problem is 2.72398, not π – 1 ≈ 2.14159.

(Desmos does all this by numerical approximation.)

Solving by hand, we would be unable to finish the work without being given a value for \(f\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\).

Of course, your work is very nice if the problem were valid, and it could be adjusted if you were given the correct value for f(π/2). Then the answer would be π/2*2.37076 – 1 = 2.72398.

I have long been interested in problems like this that can be solved to find an answer if the givens were true, but they can’t be true!

This, of course, is the topic of the present post.

Amia replied:

Thank you Dr Peterson,

If I assume f(0) = 1, f(π/2) = a

Then the question is ok?

I replied:

You’re saying, you’d just treat f(π/2) as an unknown constant a, and expect the answer in terms of that (namely (π/2)a – 1)? Yes, that would be valid.

It might make a student rather curious, though!

If I were editing the test, and wanted the problem to be valid, I might change it to this:

If f'(x) = sin(x)/x, and we know that f(0) = 1 and f(π/2) ≈ 2.37, approximate the value of ∫0π/2 f(x) dx.

The answer would be (π/2)2.37 – 1 = 2.72.

The problems we’ve seen here illustrate why I often check the premises of a problem before trying to solve it (when that’s feasible), and don’t fully trust an answer that is obtained by an elegant shortcut that skips over issues of existence.

A vacuous problem of a different sort was discussed in Assertions, Reasons, and Logic.

I welcome more examples of problems of this sort, especially any where the givens turn out to be inconsistent, though difficult or impossible to prove without advanced methods.