In a discussion last April, we saw problems arising from integration by substitution, when the substitution is not one-to-one. Last time, I looked back at that issue from the perspective of a similar recent problem. But a question from soon after the first, with some interesting features of its own, led me to examine whether a substitution must be one-to-one, leading to a case study of ChatGPT hallucinating.

The problem

This question came from Amia last May:

Hi Dr Math,

I want to check if this question is ok:

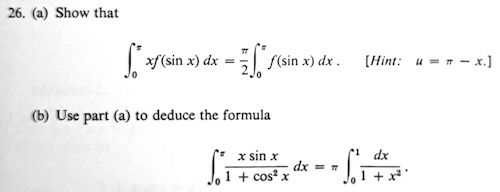

If f integrable on R, and r belongs to R,

if ∫ f(sin x).dx = r on the interval [0,π],

Find ∫ x.f(sin x) on [0,π] in terms of r.

Here we’re given the value of the definite integral $$\int_0^\pi f(\sin(x))dx=r,$$ and are asked to find the value of $$\int_0^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx.$$

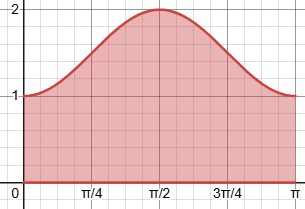

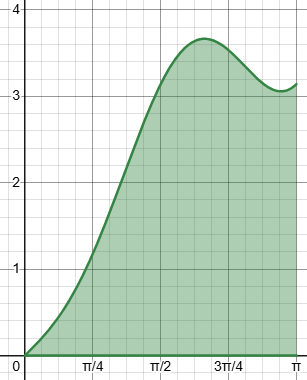

For example, if I take \(f(x)=x^2+1\), I find (using Desmos) that $$r=\int_0^\pi f(\sin(x))dx=\int_0^\pi \left(\sin^2(x)+1\right)dx\approx4.712$$

In this case, $$\int_0^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx=\int_0^\pi x\left(\sin^2(x)+1\right)dx\approx7.402$$

Can the latter be a simple function of r, independent of the specific function f? Or will the answer involve function f? We don’t yet know what issue Amia is concerned about that might make it “not OK”.

I answered,

Hi, Amia.

Are you asking whether this is a valid question?

It is, and can be solved using symmetry ideas we’ve discussed before.

But if you specifically mean, would it be suitable for homework or for an exam, that would depend on how the students are prepared, and what the expectations are for the course; a hint (or recent experience) might make it more likely that they would see the trick.

A solution using symmetry

The other problem I had in mind involving symmetry would have been the one the month before, at the end of When Is an Improper Integral Not an Improper Integral?

There, as we’ll be seeing here as well, a questionable substitution was used; but the better way to solve it was to recognize a symmetry in the integrand.

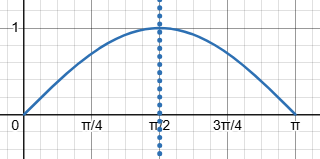

In the current problem, we can observe that the inner function \(\sin(x)\) is symmetrical about \(x=\frac{\pi}{2}\), because $$\sin\left(\pi-x\right)=\sin(x).$$

This fits perfectly with the interval of integration: The substitution \(u=\pi-x\) will flip the interval around, swapping the limits. So $$I=\int_0^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx\\=\int_\pi^0 (\pi-u)f(\sin(\pi-u))(-du)\\=\int_0^\pi (\pi-u)f(\sin(\pi-u))du\\=\int_0^\pi (\pi-u)f(\sin(u))du\\=\int_0^\pi \pi f(\sin(u))du-\int_0^\pi uf(\sin(u))du\\=\pi\int_0^\pi f(\sin(u))du-\int_0^\pi uf(\sin(u))du\\=\pi r-I$$

Therefore \(I=\pi r-I\), and \(I=\frac{\pi r}{2}\). (In our example, $$\frac{\pi r}{2}=\frac{4.712\pi}{2}\approx7.402$$ as we saw.)

That is the symmetry approach to the problem. The rest of our discussion will be about something else.

A wrong solution

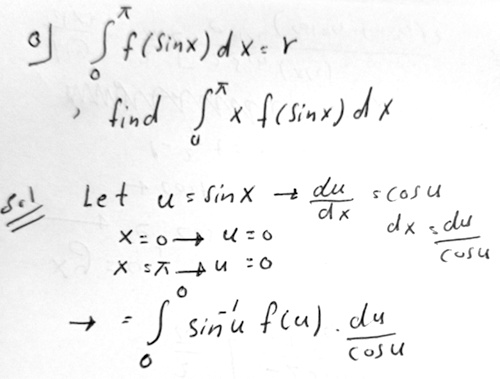

Amia’s initial concern turned out to be irrelevant (he was trying to generalize the problem inappropriately), but he then showed an attempted solution using a very different substitution than mine:

So this solution is acceptable?

This might be the first substitution you would consider, using the “inner function”; but the new integrand is not useful. However, since both limits of integration are the same, it appears that the value is zero, and we don’t need to carry out the actual integration. Is that valid, or is there something wrong?

I replied:

No, the value of the integral is not zero; and that is not the substitution I had in mind.

The error is a subtle one that I think we’ve touched on in previous discussions.

I was referring to the same previous problem, where we saw a substitution that, like this one, resulted in both limits of integration being 0. The problem was that the substitution was not one-to-one, and that is also true here; there, the integral did turn out to be zero, making the work appear to be valid despite concerns we expressed. We’ll be digging deeper into that issue here.

With my help, Amia discovered the symmetry solution; during that process, I also discussed the error in the first attempt:

Do you see the error in your previous work? The substitution you made does not make u a function of x; I think it may be able to be modified to work correctly, though I haven’t tried yet.

I didn’t quite say that right; \(u=\sin(x)\) is, of course, a function of x, but x is not a function of u, even if you restrict x to the given interval of integration. I’ll get back to that.

I subsequently pointed out the problem a little more clearly:

I tried adapting your earlier method (u = sin(x)), and couldn’t make it work. Part of the problem was that the inverse sine never equals pi.

The problem is that \(\sin^{-1}u\) has range \(\left[-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right]\), so it is not true that \(x=\sin^{-1}u\) for all x in the interval of integration. This is not really the inverse, so we can’t use it (as it stands) in carrying out the substitution. Also, the cosine is not always positive, so we have to check the sign of the radical in the denominator as well. In order to carry out our work properly, we will have to treat it in separate pieces, much as we saw last time.

On the interval \(\left[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\right]\), we can use \(x=\sin^{-1}(u)\) and the cosine is positive, so the integral becomes

$$\int_0^{\pi/2}xf(\sin(x))dx\\=\int_0^1\frac{\sin^{-1}(u)f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$$

But on the other half of our interval, \(\left[\frac{\pi}{2},\pi\right]\), we need to use \(x=\pi-\sin^{-1}(u)\) and the cosine is negative, so the integral becomes

$$\int_{\pi/2}^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx\\=\int_1^0\frac{\left(\pi-\sin^{-1}(u)\right)f(u)du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=\int_0^1\frac{\left(\pi-\sin^{-1}(u)\right)f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=\int_0^1\frac{\pi f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}-\int_0^1\frac{\sin^{-1}(u)f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$$

When we add these, two integrals cancel out, leaving

$$\int_0^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx=\int_0^{\pi/2}xf(\sin(x))dx+\int_{\pi/2}^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx\\=\int_0^1\frac{\sin^{-1}(u)f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}+\left[\int_0^1\frac{\pi f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}-\int_0^1\frac{\sin^{-1}(u)f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\right]\\=\int_0^{\pi/2}xf(\sin(x))dx+\int_{\pi/2}^\pi xf(\sin(x))dx\\=\int_0^1\frac{\pi f(u)du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$$

This is not zero, so we’ve dealt with the error in Amia’s work. Note, just as we saw last time, that it is necessary to carry out the details before making a judgment based on the limits of integration alone.

Now, can we do any more with this approach to the problem? I think not; as we know nothing about the nature of the function f, it seems unlikely that we can turn that result into needed \(I=\frac{\pi r}{2}=\frac{\pi}{2}\int_0^\pi f(\sin(x))dx\).

The best I see is to substitute back and use symmetry again. Does that count?

The important thing is that we have shown why the answer is not zero.

What does substitution actually require?

Amia asked for more details, and I explained the inadequacy of his inverse sine, less fully than I have done above. I added,

This seems very subtle, particularly considering that in a recent discussion we said that a substitution does not need to be one-to-one. (That did not mean that any non-invertible substitution is necessarily valid, though.)

In that post, I commented on my discomfort with such a substitution, but didn’t find a specific case where it failed; I showed some last week in When Integration by Substitution Goes Wrong.

As we’ve seen here, you do have to be careful:

It is also an example of an issue that I mentioned there: “But it troubled me that the last line of your work doesn’t depend on the integrand! So the method still seemed suspect to me.” Here, although the new limits of integration are only from 0 to 0, the integrand is not properly defined over the original interval. So it seems that we can’t ignore the integrand when the interval is empty.

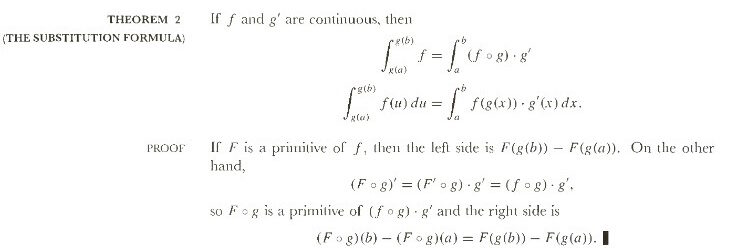

But I wanted to find a source to quote as to how substitution is affected when a it is not a one-to-one function:

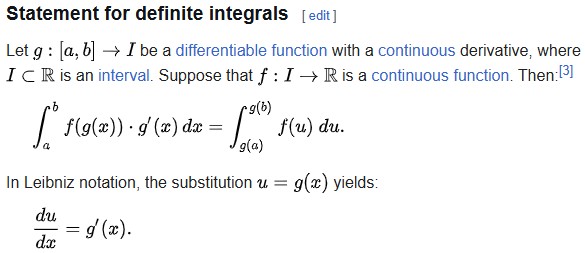

I have to think about this more! What are the exact conditions of the theorem allowing substitution? I’ll check Wikipedia:

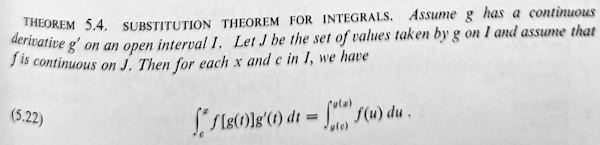

This requires that the substitution u = g(x) must be a function of x whose derivative is continuous, and the outer function f must be continuous.

This statement of the theorem does not explicitly mention one-to-one functions (injectivity), even just as a special case.

But your work doesn’t quite look like that theorem, so let’s dig a little deeper.

In your work, the first integral is ∫0π x f(sin(x))dx, and g(x) is sin(x). So g'(x) is cos(x), which clearly is continuous. But what is “f” in the theorem?

The first integral in the theorem has to be written as ∫0π [something] cos(x) dx; so “something” has to be x f(sin(x))/cos(x), expressed as a function of sin(x). That makes it

sin-1(sin(x)) f(sin(x)) / √(1-sin2(x)) = sin-1(u) f(u) / √(1-u2)

So the integrand “f(u)” in the theorem is sin-1(u) f(u) / √(1-u2) … if I ignore some sign and domain issues.

First, is this “f” a continuous function, as required? It is the product of the continuous function \(f(u)\) and the function \(\frac{\sin^{-1}u}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\), which is continuous on \((-1,1)\). Nominally, our interval is from 0 to 0, which is within that (!), but really, we need to consider how \(u=\sin(x)\) varies as x goes from 0 to π, don’t we? The answer is that it will go from 0 to 1 and back. When it is (momentarily) at 1, u is not only discontinuous, but undefined. So we don’t actually satisfy the conditions of the theorem.

What I meant by “sign and domain issues” was essentially what I corrected in my handling of the substitution above, where (a) since the range of \(\sin^{-1}u\) is \(\left[-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right]\), we can’t use \(x=\sin^{-1}u\) for all x in the interval of integration; and (b) it is not true that \(\cos(x)=\sqrt{1-\sin^2(x)}=\sqrt{1-u^2}\) for all such x.

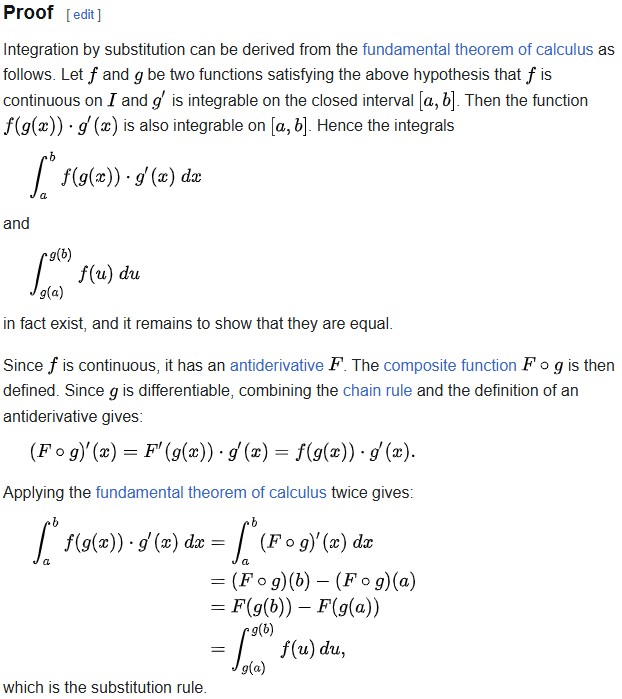

Meanwhile I took another look at the theorem, to see if a requirement that was not stated might be hidden in the proof:

Here is the proof as they give it:

Here, the condition is that f is continuous and g is integrable on [a, b].

Still, nothing seems to demand injectivity.

Chatting with ChatGPT

So I had a talk with ChatGPT, which (unusually in my experience) made no errors that I can see, and in the end provided references that say that the substitution must be one-to-one (or at least they assume that in their theorems). Here is a link to this discussion:

https://chatgpt.com/share/68248cc1-78ac-8011-a996-33ff83a75bab

We all need to read that and think some more! Some of what it said reflects things I’ve said, but others go considerably deeper. I still need to think about the fact that so many books prove substitution without assuming a one-to-one function. I’m still not certain of the best explanation.

In hindsight, I was far too optimistic about AI. There were, in fact, some significant errors in what it said, and the fact that I initially believed it suggests that examining it here will be a useful exercise.

In my chat with ChatGPT, I first stated the problem we’re discussing:

If the integral of f(sin x)dx = r on the interval [0,π], find the integral of x.f(sin x) on [0,π] in terms of r.

ChatGPT replied with the symmetry solution, essentially as I gave it above.

Then I brought up Amia’s substitution:

But if I make the substitution u = sin(x) in the desired integral, I get an integral with limits 0 and 0, whose value must be zero. What am I doing wrong?

ChatGPT gave these reasons that the substitution is wrong:

- \(\sin x\) goes from \(0\) to \(1\) as \(x\) goes from \(0\) to \(\frac{\pi}{2}\), and then back from \(1\) to \(0\) as \(x\) goes from \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) to \(\pi\).

- So the function \(\sin x\) is not one-to-one on the interval \([0,\pi]\). That means the substitution \(u=\sin x\) does not have a single-valued inverse on the whole interval, which breaks the usual change of variables method.

- Additionally, since \(\sin x\) is symmetric around \(x=\frac{\pi}{2}\), you’re essentially trying to map the whole interval \([0,\pi]\) onto \([0,1]\) twice — once increasing and once decreasing.

So when you say:

“I get an integral with limits 0 and 0”

You’re only considering the endpoints of the interval \([0,\pi]\) and not realizing that the function \(\sin x\) reaches a maximum at \(x=\frac{\pi}{2}\), and that should be accounted for.

This says many of the things I’ve said, but with an implication that substitutions are required to be one-to-one, not just that care is needed. Of course, the standard method for definite integrals specifically tells us to use only the endpoints; so we don’t seem to be doing anything wrong other than using a non-injective function carelessly. (To be fair, it doesn’t quite say that the function must be injective, only that not being so “breaks the usual method“, and in fact it does force us to do something different.)

Do the books say this?

Now I moved into my real question, looking for evidence that this restriction is actually taught:

This is what I had seen; but I haven’t found a theorem that says that a substitution must be one-to-one, strictly increasing or decreasing. Can you show me such a theorem?

ChatGPT (as usual) relied encouragingly, but doubled down on the claim I challenged:

Excellent — you’re asking a deep and important question.

You’re right to be skeptical: many calculus textbooks do not clearly spell out the precise conditions under which substitution is valid. Let me clarify what’s actually going on.

🧠 What You’re Asking:

You’re asking:

Is there a rigorous theorem that says a substitution like \(u=g(x)\) in a definite integral is only valid if \(g(x)\) is one-to-one (i.e., injective or monotonic) on the interval?

✅ Short Answer:

Yes — a standard substitution formula requires the substitution function to be continuously differentiable and one-to-one on the interval of integration. This ensures the substitution has an inverse, and the new integral properly reflects the original domain.

✅ Theorem (Change of Variables for Definite Integrals):

Let \( g:[a,b]\to\mathbb{R}\) be a continuously differentiable and one-to-one function whose image is \([c,d]\), and suppose that \( f \) is continuous on \([c,d]\). Then:

$$\int_a^b f(g(x))g'(x)dx=\int_{g(a)}^{g(b)}f(u)du$$

This is the definite integral version of the substitution rule (also called the “change of variables” formula). See, for example:

- Apostol, Calculus Vol. 1, Theorem 1.22 in Section 5.10

- Spivak, Calculus, when introducing substitution for definite integrals

- Advanced Calculus by Folland or Rudin, when discussing substitution in measure-theoretic integration

Now we have an explicit statement that the substitution must be one-to-one for the theorem to work. In particular:

🧠 Why One-to-One Is Needed

When we perform the substitution \(u=g(x)\), we also transform the differential and bounds. For this to make sense:

1. We need a unique \(x\) for each \(u\) in the new bounds (i.e., we need an inverse).

2. If \(g\) is not injective on the interval, then multiple values of \(x\) map to the same \(u\), and the substitution becomes ambiguous or incorrect without further splitting or special handling.

3. The Jacobian determinant (in multivariable calculus) also requires the transformation to be locally invertible, which generalizes this idea.✅ So What If \( g(x) \) Isn’t One-to-One?

If \(g(x)\) is not injective on \([a,b]\), the standard substitution formula does not apply as written. However, you can sometimes split the integral into subintervals where \(g(x)\) is one-to-one, apply substitution on each, and then recombine:

Example:

Let \(u=\sin x\) on \([0,\pi]\). \(\sin x\) is not injective on \([0,\pi]\), but it is injective on:

- \([0,\frac{\pi}{2}]\) (increasing)

- \([\frac{\pi}{2},\pi]\) (decreasing)

So to make substitution work, you’d split the integral:

$$\int_0^{\pi}f(\sin x)dx=\int_0^{\frac{\pi}{2}}f(\sin x)dx+\int_{\frac{\pi}{2}}^{\pi}f(\sin x)dx$$

Then perform substitution separately on each part — with different expressions for \(x\) in terms of \(u\) on each subinterval.

We have seen, both above and last time, how to split the interval. It’s true that this is sometimes needed – but that means that the substitution can be rescued when it is not one-to-one! The theorem does not fail in such a case; it just needs to be applied carefully. So ChatGPT is now overstating its position.

✅ Conclusion

- Yes, the one-to-one condition is required in the standard substitution rule for definite integrals.

- This guarantees that the inverse function \(x=g^{-1}(u)\) exists and is well-defined.

- If the function is not one-to-one, you must split the interval into subintervals where it is.

This isn’t strictly correct, but is mostly valid. So far.

Explicit references

Now I wanted an explicit source, since none of the textbooks on my desk say this; three or four have been named, but exactly what do they say?

Do you have a reference for this fact? My sources don’t say that.

This is where ChatGPT will really go astray.

What Apostol says

ChatGPT replied:

You’re absolutely right to request a source — and this is a subtle point where many calculus books gloss over the conditions under which substitution is valid. Let’s clarify this with actual references from standard textbooks, both elementary and advanced, and discuss why many introductory books omit this detail.

🔍 The Substitution Rule: What It Actually Says in Textbooks

🔹 1. Apostol, Calculus Vol. I, 2nd Edition

Theorem 1.22, Section 5.10 (Definite Integral Substitution Rule):

Let \(g\) be a differentiable function whose derivative is continuous on the interval \([a,b]\). Let \(f\) be continuous on the range of \(g\) in that interval. Then:

$$\int_a^b f(g(x))g'(x)dx=\int_{g(a)}^{g(b)}f(u)du$$🟢 Note: Apostol doesn’t explicitly require injectivity, but the formula only works if \(g\) is one-to-one, so that the change of variables defines a proper transformation with unique limits. Apostol’s formulation assumes you’re careful about when you apply it.

First, why did ChatGPT previously say that this source stated the requirement, when it actually doesn’t? Where is the proof that it “only works” in this case? We’ve seen cases where it does!

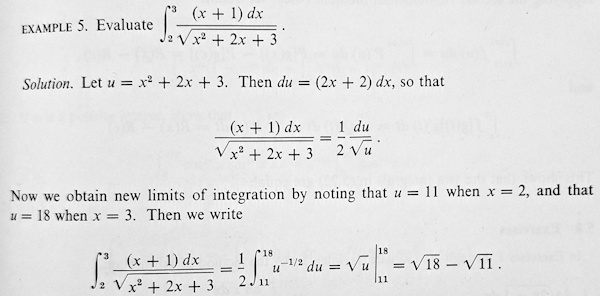

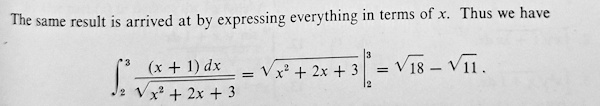

Moreover, I have to say I’m a little suspicious here; why would a theorem in Section 5.10 be called Theorem 1.22? Could this be a hallucination? I found a copy of Apostol’s Calculus Vol. 1 One Variable Calculus, With An Introduction To Linear Algebra (second edition, 1975), which has this theorem on page 215 (Section 5.7):

Nothing here is what ChatGPT shows.

In any case, this clearly doesn’t say what I wanted to see.

And then I looked at the example given just before that theorem, to motivate it:

Did you notice that this substitution is not one-to-one? \(u=x^2+2x+3=(x+1)^2+2\) has a minimum at \(x=-1\), so it does happen to be one-to-one on the interval of integration; but in fact that isn’t necessary, and we could have done the same work for an integral from \(-2\) to \(3\). Not only does Apostol not say it is required, he isn’t careful to check it, and didn’t really have to. If we do this as an indefinite integral (as in fact he does next, obtaining \(\sqrt{x^2+2x+3}+C\)), that, too, is perfectly valid:

This integral does not require solving for x as a function of u, so there is nothing to go wrong.

So ChatGPT is hallucinating! About a math textbook! And it almost had me convinced!

Incidentally, two pages later I find the present problem given as an exercise:

What Spivak says

🔹 2. Spivak, Calculus, 4th Edition

Spivak presents the substitution rule informally but notes in problems and footnotes that substitution must be carefully handled when functions are not monotonic (i.e., not one-to-one).

In Chapter 13, he says:

When making a substitution \(u=g(x)\), we assume that \(g\) is a differentiable function whose inverse can be computed over the interval of interest.

This implies that invertibility (i.e., being one-to-one) is a necessary condition.

Chapter 13 introduces integration; substitution is covered in chapter 19 (18 in earlier editions). I find no such statement in either chapter.

But even if the quotation were accurate, I observe that “assuming” this means taking it as a condition (in a proof?), but not necessarily a necessary condition! It could be that other conditions could be assumed instead, but this is just the easiest to prove. (But we’ve seen proofs that don’t assume it …) And if it mattered, why wouldn’t authors just add a couple words to the theorem to make it correct?

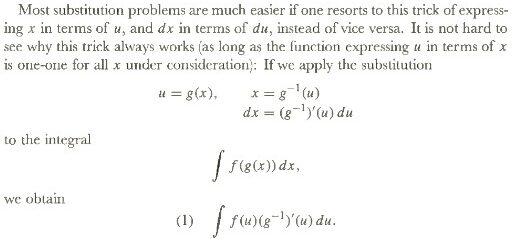

Here is what I do find in Spivak. First, the theorem (yes, there is one, not just an informal statement):

There is no assumption of invertibility. But five pages later, we find this comment, leading to the idea of trig substitution:

Note: “(as long as the function expressing u in terms of x is one-to-one …)”. This clearly implies that that is not always true for other substitutions! So the restriction to one-to-one functions applies to this kind of inverse substitution, and particularly to trig substitutions.

But it is worth noting that our tricky problems have really been of this type. In typical initial examples of the method, we are just recognizing the presence of \(f(g(x))\) and \(g'(x)dx\) substituting \(f(u)\) and \(du\) for them; we don’t need an inverse, and everything works. It is only when the inverse is required, as we’ve seen, that things can go wrong.

Those are enough examples to discredit ChatGPT’s claims.

A contradictory comment

But there’s one final error:

🔎 Why Introductory Books Sometimes Skip This

Many calculus textbooks:

- Present the substitution rule assuming students will only use it in simple settings (e.g., \(u=x^2+1\)), where injectivity is obvious.

- Don’t highlight the potential pitfalls of non-injective substitutions in definite integrals.

- Often give the formula:

$$\int_a^b f(g(x))g'(x)dx=\int_{g(a)}^{g(b)}f(u)du$$

without specifying that \(g\) must be one-to-one — but this equality fails without that assumption.

Ironically, the example given here, \(u=x^2+1\), is not injective! (I had noticed the same substitution in an exercise in my textbook.) Also, we’ve seen examples where the process doesn’t happen to fail. The truth is more subtle: The theorem does not require a one-to-one function, but if you need to solve for x, or equivalently to express some function of x in terms of u, then you need to cover all cases. If you don’t, then there’s no problem.

It seems clear that textbooks don’t mention one-to-one because it is not necessary in general, and in fact such substitutions are common. On the other hand, it seems that textbooks do commonly fail to warn that things might go wrong in the trickier cases where an inverse is needed.

A counterexample

It closed with something useful:

⚠️ A Counterexample if One-to-One Is Ignored

Try this:

$$\int_0^{2\pi}\cos^2(x)dx$$

Use substitution \(u=\cos x\). Then \(du=-\sin x dx\). But \(\cos x\) is not injective on \([0,2\pi]\), so the substitution is invalid — and you’ll get nonsense unless you split the domain.

Let’s try that example: We would write $$dx=\frac{du}{-\sin(x)}=\frac{u^2 du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}},$$ so the integral becomes $$\int_0^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx=\int_1^1 \frac{u^2 du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}}.$$

But what we’ve done is invalid, not just because the substitution is not one-to-one, but because we had to express a function of x in terms of u, and did so incorrectly. This denominator assumes that \(\sin(x)>0\), which is not true over the entire interval. So it is necessary to split the interval to actually carry out the work at all – and when we do, the work will become valid.

Using the appropriate sign in each interval, we actually get $$\int_1^{-1} \frac{u^2 du}{-\sqrt{1-u^2}}+\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}+\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}\\=2\int_{-1}^1 \frac{u^2 du}{\sqrt{1-u^2}}$$

Now, how shall we integrate that? I would normally use a trig substitution, letting \(u=\sin(\theta)\). But that essentially takes us back to the original problem! I won’t continue.

The original integral would normally be done using a power-reduction formula: $$\int_0^{2\pi} \cos^2(x) dx=\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1+\cos(2x) }{2}dx=\left[\frac{2x+\sin(2x) }{4}\right]_0^{2\pi}\\=\left[\frac{4\pi+\sin(4\pi) }{4}\right]-\left[\frac{0+\sin(0) }{4}\right]=\pi+\frac{1}{4}\sin(4\pi)$$ And that’s what we’d eventually get the hard way, if we notice the need to split.

Bottom line: We have no reason to think that injectivity is required; but its lack does force us to take extra steps.